Whatever your opinion on pink mustaches, you’ve probably noticed ride-sharing’s been heating up over the past year.

What’s the difference between Uber, Lyft, and everyone else?

Why does supply matter?

Ride-share companies like Uber, Lyft, Sidecar, and dozens of others have been controversial from the start. Do they have the right insurance? Is it safe? Who’s liable when things go wrong? And of course, what’s going to happen to taxis?

These are all great questions, and they’ve already been pondered extensively in the articles linked above and elsewhere on the Internet.

So today I’d like to focus on the economics-side of things.

As most of you already know, mobile ride-share apps hail cars from your phone, keep track of how far you’ve gone using your phone’s GPS, and handle payments when the ride’s over.

These companies like to differentiate themselves with everything from fist-bumps to happy hour-esque discounts. But at the end of the day, there really is no difference. You request a car from your phone. You get in the car. You arrive at destination. You get out without worrying about paying the driver.

That’s not to say the minor details like pink mustaches and free bubbly water don’t matter – they significantly impact each company’s brand identity. But I like to think of these nuances as more of a cultural thing, not unlike the once-raging Apple vs. PC debate, rather than a substantive difference across competitive products.

It would make sense then, that you, the omnipotent customer, care most about just two things: price and convenience.

In other words, you want a ride as soon as possible, and you don’t want to pay too much for it.

So it makes sense that the major ride-share players have ramped up driver recruitment to build out their networks (for your convenience) and slashed fares across the country (to decrease price).

This leaves you in a pretty great spot. Sign-up bonuses are everywhere. Pricing wars have essentially driven the price of a ride below what it costs to take a taxi. And since you can access multiple ride-shares in most cities, you can just shop around until you find the one that’ll arrive the soonest. The closest Uber is 10 minutes away? No worries, just click on over to Lyft and get one in 3.

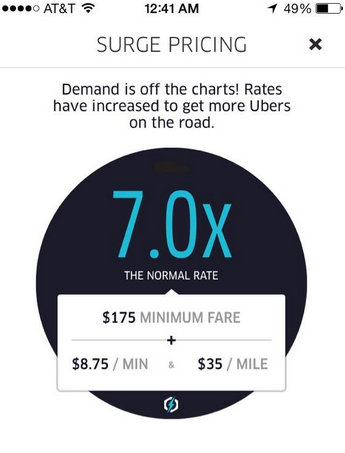

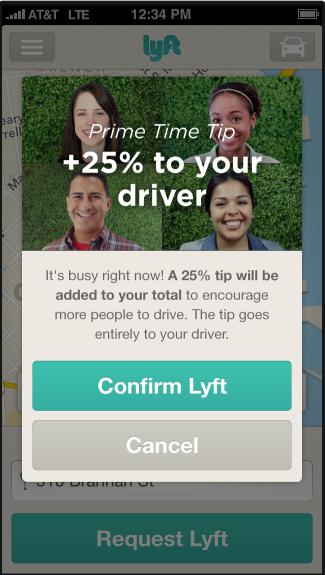

Things are going great, until you run into the screen of you-know-what. It’s what sends chills down the spine of anyone caught in the rain and infuriates drunk party-goers around the world:

During times of peak demand (usually during rush hour, when it rains, or right after bars close), ride-share prices multiply dramatically, ostensibly to encourage more drivers to get on the road.

You can see how our preferences for low prices and greater convenience are inherently linked. The more cars out there, the sooner we’ll get picked up, and the cheaper it’ll be. If there aren’t that many cars, the opposite should hold true, because economics.

But it’s not as simple as manufacturing more supply, because drivers want to get paid too. Most of your fare goes directly to your driver, so a decrease in fare will directly lower your driver’s wages.

When Uber slashed its UberX prices in NYC and locked many of its black cars into this lower price (read: wage) tier, drivers were pissed. And that’s not just in New York. Drivers across the country are protesting Uber’s pricing schemes, with a “global” protest scheduled for next week.

A new ride-share company called Gett is looking to take advantage of this driver discontent, luring Uber drivers with promises to double their pay per minute. Since drivers can work for more than one of these ride-share companies, they’ll presumably stick with the one that pays the most.

So for the Ubers of the world, figuring out how to attract the most drivers, or increasing supply, is the number one priority moving forward.

Demand will always be there. People have needed to get from Point A to B since forever, and taxis have done okay so far. But the convenience of mobile-enabled ride-sharing is hard to deny, and I fully expect demand to only increase in the future.

This all puts ride-share companies in a bit of a conundrum. How do they attract customers with low prices while still satisfying their drivers’ income expectations? How do they convince drivers to partner with them and not one of their many competitors? How can they possibly expect to turn a profit with vanishing margins?

The answer to all of these questions has to do with supply. A larger labor market will drive wages down, creating the low prices we all want – even as the ride-share company pockets their cut. A greater pool of interested drivers will also allow ride-share companies to be less picky or eager in recruiting new drivers.

Where will all this supply come from? Here’re some possible categories:

- New drivers: All of the major ride-shares allow anyone with a valid license and a relatively clean background sign up to be a driver. Flexible working hours and salary guarantees certainly help convince those on the fence.

- Competitors: From cheeky ads to allegedly unsavory tactics, ride-shares aren’t afraid to bash their competition to poach drivers.

- Professional drivers: Several ride-shares work exclusively with licensed livery providers, and companies like Gett are clearly targeting drivers disgruntled with the down-market trend the major ride-shares have been following.

The problem is no one really knows which category will produce the most drivers. That’s why you see Uber and Lyft sourcing drivers from all three categories with equal vigor. Until one pool emerges as the clear winner, building up supply will remain ride-shares’ most significant challenge in the upcoming years.

That is, until you see one of these on a street near you: