Okay, that headline is overpromising just a bit. We can’t tell you how to win your March Madness office pool, but we can tell you how to improve your odds a bit.

To start, you need a good way of ranking the teams. The NCAA tournament committee seeds the teams using RPI, but RPI doesn’t work as well as it should. The true test of how good your team rankings are lies in their predictive value, and on that measure Ken Pomeroy’s ratings are the best we’re aware of.

There’s a fascinating article at the Harvard College Sports Analysis Collective which delves deeper into the issue. The author of that article looked at how RPI has performed vs the Pomeroy ratings for the past six years, and then added in his own survival model which incorporate Pomeroy’s numbers and adds other factors. The results:

Here are last year’s Survival Model rankings. They were released the day before the tournament last year, so if you’re gung-ho about winning your pool, it might be worth checking the HCSAC blog the next few days.

Another principle to keep in mind: avoid bias. We tend to have higher opinions of things we’re familiar with, and NCAA pools are no exception. If the people in your pool live in, say, Indianapolis, more people will pick Indiana than would be justified by the team’s chances of winning. Even if you’re a one seed, you’ve got about a 50-50 chance of making the Final Four.

So if you’re a Hoosier, you can increase your odds by picking against the Hoosiers. You have little to gain by picking them, since everybody else will already be picking them, but if they lose before the Final Four–and remember, there’s a very good chance they (or any other team) will–you stand to gain significantly if you called it and nobody else did.

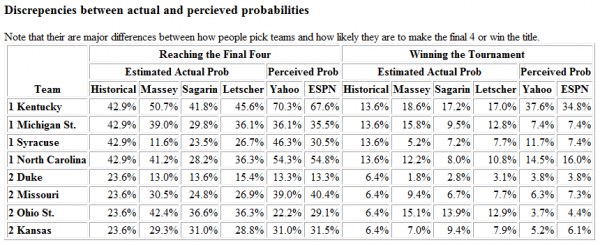

A related principle: people tend to pick 1-seeds more than they should. It’s the familiarity bias again, plus the fact that it’s just hard to pick against the 1-seeds. After all, they usually are the best teams in their region. Here’s an interesting table based on last year’s team which illustrates what we’re talking about:

You’re not trying to pick the best teams; you’re trying to pick teams where the actual probability of winning the tournament is greater than the perceived probability. The numbers above are from last year. Granted, Kentucky actually did win, but we’ll also point out that while 55% of the population expected UNC in the Final Four last year, the Tar Heels did not make it. If you didn’t feel comfortable picking against an overwhelming favorite like Kentucky was in 2012, you could have picked them to win but then picked UNC to get upset.

To avoid bias with your own college, you may want to consider emotional hedging. This is the practice of picking your team to lose earlier than you think they will. It’s a win-win situation for you: either they advance past where you picked them, or else they lose early but their loss doesn’t screw up your pool.

Try to take advantage of any quirks of your pool’s rules. For example, suppose your pool offers double points if you correctly pick a lower-seeded team to defeat a higher-seeded team. The 8-9 game is usually a coin flip, so you’d probably want to pick the 9-seed in all 8-9 games.

Have fun, and good luck!

Recent Comments