Your retirement number is the amount that you need to have saved in order to retire. I want to dive into this today and explore some really important things that come along with this. I’m going to define it ‘my way’ and bring in concepts such as the Investment Policy Statement, asset allocation, risk taking, and goal setting.

Limitations of the Retirement Number

The actual calculation of your number will always be somewhat of an educated guess. We are trying to gaze into the future and guess at our expenses. The trouble with this is that expenses are influenced both internally (how much you decide you need or want) and externally (how much the price changes due to supply, demand, innovation and inflation. You’re also going to have to take a guess as to how long you expect to live, and decide whether you want to leave a financial legacy, or spend up all your resources.

For these reasons, even though we attempt to define a fixed number, it will always be a fixed number coupled with a likelihood of success. Success being measured in how likely it is you have to get a job in McDonalds at the age of 78 in order to maintain your lifestyle.

Limitations aside, the knowledge is a powerful thing. Knowing what X is creates a ‘financial destination’ and the foundation of a roadmap to get there.

Calculating the number

- Years in retirement x Cost of Living Adjusted (COLA) Amount needed per year

Years in retirement is a combination of what age you enter retirement, and what age you expect to die. The COLA amount should factor in other sources of income, such as social security and private pensions. Note that small changes can have a ripple effect. For example, if you elect to retire at 50 then your social security average will be reduced, so you’ll not only need to save more for a longer period, but also save more to make up that shortfall.

Warning – don’t aim low!

Even conservative investors sneak in ‘low numbers’ in this calculation. For example, they put inflation at current levels, which at this time are close to zero. It is better to look at historical rates, which may be around 3%, and also model further- what happens to your plan if inflation hits 4%? Likewise, for longevity.. while you should certainly consider family genetics, you should also consider how advancements in medical science are helping extend longevity. Most plans that I see now are shifting from an age of 90 towards an age of 95.

What do you do with your data?

Once you have your data, you can calculate your ‘number’. The math is basically an annuity calculation. You can play around with calculators online to see how things change. Here’s a basic one from Bankrate. Let’s look at example to explore the data further:

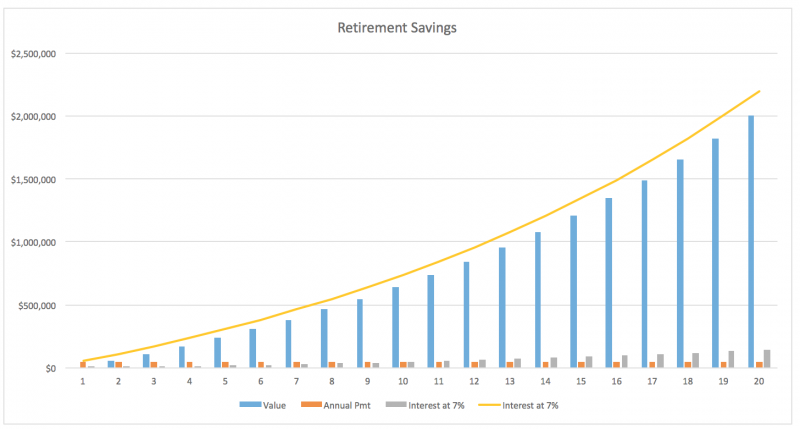

If I wanted to retire at 50 and take a $50,000 annual payment I’d have a retirement number of $2.06M saved 12 years from now. That assumes a 4% inflation rate and a 7% investment rate of return (2.88% inflation adjusted return). This is where things get interesting….That number today would be around $900K. That means if I had $900K saved today, I could retire at 50… it doesn’t mean that I could retire today on $900K saved because I would run out of money on the back end. But, it does mean that I wouldn’t need to put anything more into the fund in order to retire on target.

Building an Investment Policy Statement (IPS)

Your IPS is a document that is used to keep you on goal. Basically you sit down when you are of sound mind and write out what you want to achieve from your investment strategy. In my case here I would write down that I want to save $2.06M by the age of 50. I’d have to decide upon a risk tolerance level for my investments that got me there soundly, and in rough market patches refer back to this statement to keep me level headed.

But what happens when things go really well? If we look back, we are enjoying one of the longest running bull markets of history. What has that done to projections and investment policies? What do we do when we are ahead of the game?

Let’s say my IPS was set back at age 30. I decided that I want to save $2.06M by age 50, and I would be willing to build a portfolio of investments that offered a balanced return for my annual payments. I could calculate that I’d need to save $50,000 per year at 7%.

Reality of actual returns

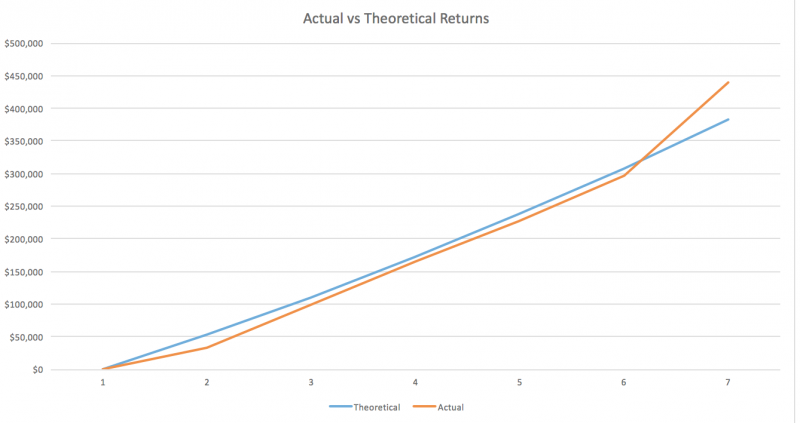

The chart above is a pretty model, it shows a linear path to goal based upon forecasted results. However, the reality is that if you are invested in assets other than fixed income, your chart isn’t going to look like that at all. So what happens when things go differently? Let’s look at the same 30 year old, using real return data. For sake of simplicity I’ll just use the DJIE. Taking this year to date, we have a real return ahead of the plan.

What to do now?

Some people say that you should ‘stick to your IPS’ throughout. But where is the sense in that? If you were anticipating an average annualized return of 7% for the amount of risk you have, and you have exceed it, why keep the same risk level? The goal didn’t change, here we still have a person who wants to retire by 50, but with the current IPS he is ahead of the game.

Something needs to happen.

If you just keep with the original gameplan you will be off base. So if you really want to keep your retirement age at 50 you should make a decision to throttle down your investment growth. This can happen in one of two ways:

- Reduce your annual payments, keep the same risk/return profile

- Maintain your annual payments, adjust your risk/return profile

Behaviourally, the former is a dangerous option, as it encourages an increase in spending. If someone has been able to maintain $50,000 annual payments for years, they ‘won’t miss it’ if they keep this up. However, a reduction of payment will likely cause lifestyle inflation. Maintaining the payment, assuming that all other things on the balance sheet remain equal, should be manageable. And reducing risk means that if things do regress to the mean (which they ought to at some point within the 12 year investment horizon) the portfolio will have less impact from it.

Behavioural factors

When we explore this concept of being ahead of plan we bring up a lot of great thoughts. Some of them might be:

Why not let it ride? We could make even MORE money! This one is a great example of not having a plan. It shows that your goal wasn’t right in the first place. If I had really wanted $2.5M at age 50 so I could vacation twice a year, the that should be baked in at the planning stage. The goal in wealth accumulation is to risk absolutely as little as possible in order to reach goal.

What about retiring before 50? This is an interesting angle. If you just stick to plan you may be able to retire sooner than plan. It sounds good… but it also sounds sloppy. If you really want to retire at 49 why not model it out again? We know that we are about $60K ahead of schedule, what does that actually mean to your plan?

Conclusion

If we start thinking about a firm retirement number we can calculate the payment required to achieve it, and the rate of return needed to help get us there. An IPS will be the tool that we can use to keep us level headed when the markets are down, but when they are up, should we take a moment to decide whether we still need that much risk? From my experience, people who have a significant amount of money are looking for less risk and more consistency, whereas people who are working their way up are willing to take risks to get to goal. Perhaps we should reflect on the amount of risk we actually need in order to reach the goals we set a few years ago?