I started this blog because the more I learned about the personal finance industry, the more I saw the same problems that are pervasive in my other line of work in the travel hacking community: people are either paid to lie, or too ignorant to know if what they’re saying is true or not. So, I figured I’d start a blog where I could tell people the truth.

One difference between personal finance and travel hacking is that personal finance has an unusual number of people who are not being paid to lie, but for one reason or another are also incapable of telling the truth.

Jason Zweig and the amazing disappearing advice

I started thinking about this last week while researching some recent Wall Street Journal columns by Jason Zweig. At least as early as February, he started writing about the fact that by shopping around you could earn more interest on your savings that the rate offered by the big national banks and on mutual fund settlement accounts offered by brokerage houses. This is true.

But this is a meaningless observation if it does not rise to the level of advice. Consider the following passage:

“Many money-market mutual funds are paying 2% and up. Although they aren’t backed by the government, they hold short-term securities whose value tends to hold steady. (A money fund yielding much more than 2.5%, however, is probably taking excessive risk.)

“At Vanguard Group this week, taxable money-market funds were yielding between 2.31% and 2.48%, and tax-exempt money funds yielded 1.19% to 1.32%. Fidelity Investments and Charles Schwab Corp., among other firms, also offer money-market funds with attractive yields.”

This looks very close to advice, but the more closely you read it, the more you find it slipping through your fingers. It is true that Vanguard taxable money-market funds were yielding “between 2.31% and 2.48%.” But this is an absurd way of framing the situation. Vanguard only offers two taxable money-market funds! They are:

- Federal Money Market (VMFXX), yielding 2.34% as of March 19, 2019.

- Prime Money Market (VMMXX), yielding 2.45% as of March 19, 2019.

What is the point of describing this situation as a “range” between yields on Vanguard money-market funds? If you are saving cash in a Vanguard account, and can meet the $3,000 minimum investment requirement, you should put it in the Prime Money Market fund. If not, you can use the Federal Money Market fund (which is also the settlement account for Vanguard brokerage accounts, so it’s not like you have a choice). If your current brokerage offers less than that on your cash, you should move your cash to Vanguard.

Zweig then turns to online savings accounts, and mentions Goldman Sachs’s “Marcus” online savings product: “Savings accounts at Marcus, the online bank operated by Goldman Sachs Group Inc., are paying 2.25%, with no minimum investment required. It takes only a few minutes to open an account; U.S. deposits at Marcus grew in 2018 by 65%, to more than $28 billion.”

Again this at first appears to rhyme with advice. Why would he mention Marcus if he isn’t advising readers to use Marcus? But 2.25% isn’t the highest interest rate you can earn on an online account: All America Bank offers 2.5% on up to $50,000 in their Mega Money Market Checking accounts!

Education may be valuable, but most people need (good) advice, not education

Let’s turn from the Wall Street Journal to that other bastion of financial erudition, Bloomberg Opinion. Barry Ritholtz, the namesake of extremely-online financial advisory Ritholtz Wealth Management, last week expressed his anxiety over the extremely poor protections enshrined in law for participants in retirement plans offered by non-profit organizations and state and local governments, so-called 403(b) plans (which I’ve had occasion to write about before).

These extremely inadequate protections are no doubt a matter of serious concern. But a teacher searching the internet for information about her 403(b) account does not need to lobby Congress to extend ERISA protections to 403(b) accounts. She needs advice about what to do with her 403(b). And just in the case of Jason Zweig, you can begin to see the glimmer of advice in Ritholtz’s article. He writes:

“403(b) plans tend to invest way too much money in annuities — 76 percent on average. Annuities have much higher costs than typical mutual funds.”

And:

“If an employer and 401(k) plan sponsor put a high-cost, tax-deferred annuity into a tax deferred 401(k), they would be warned by counsel to expect litigation.

“And they’d probably lose, because paying a high fee to put a tax-deferred component into a tax-deferred account is pointless.”

Now, if you squint at these statements closely enough you might be able to guess that Ritholtz is saying “don’t put a high-cost, tax-deferred annuity into your 403(b),” and “invest less than 76% of your 403(b) account in an annuity.”

But why should it be that people are left guessing in the first place?

People who provide information don’t provide advice, and people who provide advice don’t provide information

This is the fundamental pattern I see over and over again in the world of personal finance. Take, for example, my favorite resource for mostly-up-to-date interest rate information, DepositAccounts. This is an excellent resource I use constantly to check on interest rates on rewards checking accounts, online savings accounts, CD’s, and money market accounts. Go ahead and bookmark it, if you haven’t already.

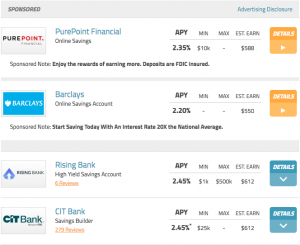

But this is what the top of their “Savings Accounts” page looks like (in my ZIP code):

Now, this is obviously absurd: why would anyone prefer an account with a $10,000 minimum paying 2.35% over an account with a $1,000 minimum paying 2.45%? But DepositAccounts found a couple banks willing to pay them for preferred placement, presumably because those banks, rightly or wrongly, calculated that preferred placement would attract deposits in excess of their account’s objective appeal.

Conclusion: always look for what’s not being said

It would be awfully odd to end a post like this without offering some concrete advice. Indeed, I’d be guilty of exactly what I accused Ritholtz of: educating without advising.

So let me sum up my advice in the most concrete way possible:

- When you are reading a piece of financial journalism, pay close attention to what is not being said. If someone says you “can” increase the interest rate on your savings, or you “can” reduce the expenses you pay on your investments, check whether they also say you “should” increase the interest rate on your savings, or you “should” save money on management expenses. If not, why not? Does the publication have relationships with investment managers they don’t want to jeopardize?

- When you’re reading a source of information like DepositAccounts, the same rule applies. If a particular account is “sponsored,” or a partner is “preferred,” or a bank is “recommended,” are you given any reason why that account is superior to any other account? Are there other, better accounts that are excluded because they are unwilling to pay for placement, or don’t pay a commission to the site?

I’ve written elsewhere that many people make a grave mistake when compensating for conflicts of interest. They think, “now that I’m aware of the conflict of interest, I’ll discount it by an appropriate amount.” But this is incorrect. The correct response to a conflict of interest is to discount the advice given by 100%. If possible, you should even discount conflicted advice by slightly more than 100% (this is not always possible, for example in insurance sales where some kind of commission is typically unavoidable).

The United States has some of the most vigorous protections for free speech in the world. It also has some of the most strict restrictions on professional speech, and a national media almost entirely in the control of a few powerful corporations and individuals. This curious contradiction often makes it difficult or impossible to know whose voice you’re hearing at any one time: when is Jason Zweig speaking for Jason Zweig, when is he speaking for the Wall Street Journal, and when is his voice filtered through the Journal’s legal department? But it is still possible, and necessary, to figure out when, for whatever reason, you’re not getting the whole story and to try to put the pieces together for yourself.

Good read!

“when is his voice filtered through the Journal’s legal department?”

Well, always. Every time he hits Submit.

Just kidding, I know what you mean.

As someone who’s trying to make a living as a freelance writer, I could tell you a story or two about ridiculous things Legal kills on a daily basis. I would presume it gets even tougher when a journalist is trying to act as an adviser. Then again: hard to blame them in a society where you can sue a hamburger for hurting your feelings.

Which is why you tip is right on the money: Look for what’s NOT being said.

Love your blogs!

“Your” tip, LOL