When ignorant people want to sound serious, they start solemnly intoning about the Social Security funding crisis and the need for a “long-term” “fix” to the “problem.” This serves three useful purposes: it allows the speaker to change the subject from any actual problems existing today, it provides the superficial cover of concern for vulnerable populations, while also giving a sheen of non-partisanship to plans that will decimate the working class.

This makes it extremely important to understand what the Social Security funding “crisis” will look like in the real world.

Nothing at all will happen until 2034

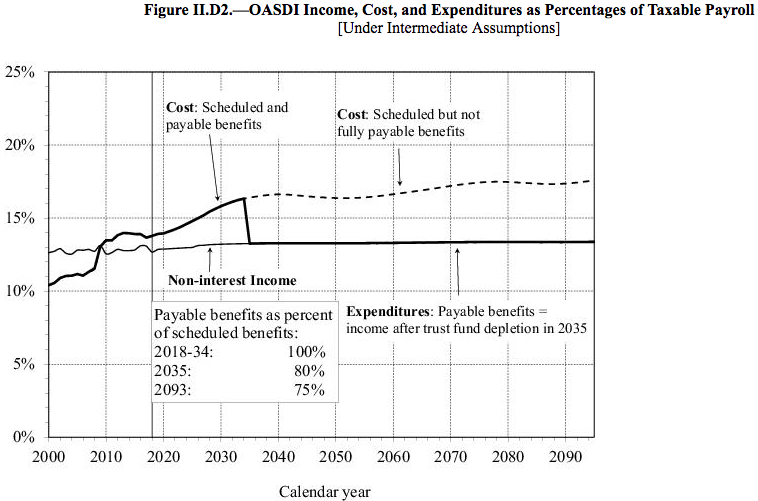

The most important chart to understand in the Social Security Trustees’ report is Figure II.D2, which I’ll reproduce in its entirety:

What this chart says is that until 2034, under current law, with no additional benefit cuts or additional taxes or funding streams, the Social Security Administration is projected to be able to pay 100% of scheduled benefits, including old age, disability, and survivor benefits. So whether or not any changes are made to Social Security, nothing will change for any new or existing beneficiaries for the next 15 years.

If you are not a current beneficiary, or planning to begin receiving benefits soon, you may find this pedantic, but if you’re already receiving benefits you should know: under current law your benefits will not change in any way for the next 15 years.

What happens after 2035?

After 2035, the Social Security trust funds are projected to begin exhausting the Treasury bonds they accumulated during the years the funds took in more money than they paid out in benefits. Unlike a private company that does not receive enough income to repay its debts, the Social Security Administration cannot, and does not have any need to, “declare bankruptcy” or “go bankrupt.”

Instead, as Figure II.D2 shows, benefits will be reduced to the level payable through annual payroll contributions. In 2035 the actuaries predict there will be a 20% reduction in payable benefits, which will increase excruciatingly slowly to a 25% reduction by 2093.

This is an important moment to remind you that the exhaustion of the trust fund cannot “reduce your promised benefits,” because these are the benefits promised by the Social Security Act, as amended. If you’re happy with 20-25% lower benefits in old age, disability, or widowhood after 2035, you don’t need to do anything and you don’t have a dog in this fight.

Should we allow this benefit cut to take place in 2035? Probably not!

If, like me, you think the American welfare state is not generous enough then, like me, you probably don’t think we should suddenly cut Social Security benefits in 2035.

But if you think the American welfare state is not generous enough, then you have the luxury of other, lower-hanging fruit. The Trump administration is planning to reimpose a cumbersome asset test on SNAP beneficiaries nationwide, denying 3.1 million people access to nutritional assistance. Another 500,000 elementary and secondary students are expected to lose access to free school lunches.

Meanwhile, Republican officials are using a laughable legal argument to pursue the invalidation of the Affordable Care Act, including its protections for pre-existing conditions, subsidies for low-income workers who don’t receive health insurance through their employers, and Medicaid expansion. And thanks to the Republican effort to amateurize the judiciary, there’s no reason to believe they won’t win in front of the Gorsuch-Kavanaugh Supreme Court.

If you’re elevating a fantasy problem in 2035 over the real problems we’re facing right now, your priorities say a lot about you and nothing about Social Security’s funding mechanism.

My boring solution to the imaginary Social Security funding crisis: magic it away so we can address real problems

The total funding shortfall between now and 2093, in the Social Security Trustees’ actuarial report, is a bit under $14 trillion, or $186 billion per year for the next 75 years.

So here’s my boring solution: let’s round up, and deposit $14 trillion in special issue Social Security bonds into the relevant trust funds, out of nowhere. This will, of course, increase the debt service costs of the US government as it pays interest on those bonds, and that increased cost will need to be financed through reduced spending, increased taxes, or seignorage.

But this is, of course, the exact issue the Social Security funding “crisis” is supposed to present: should we reduce spending, increase taxes, or print money? It may be that we should reduce Social Security benefits, especially for higher earners. It may be that we should increase them, especially for low-income workers and those with a limited official work history.

But since there’s obviously no reason Social Security benefits should be tied to the year-to-year revenue produced by FICA taxes, we can easily make sure they aren’t.

Conclusion

In reality, no one in politics wants to solve the imagined Social Security funding “crisis.” When the Greenspan amendments to the Social Security Act were made under Reagan, they were explicitly designed to create another funding crisis further down the line, so that benefits could be cut further.

Whether we want benefits to be cut or not is up to us. We can eliminate the cap on Social Security taxes and treat capital gains and dividends as ordinary income and eliminate the “funding gap” tomorrow. Some of us support those policies, others oppose them, but no one should support or oppose those policies because of their downstream effect on Social Security benefits: whether or not Social Security benefits are suddenly cut 15 years from now doesn’t have anything to do with the program’s funding mechanism.

Rather, it’s a question about who we are and what kind of country we want to live in. That’s the question Roosevelt had to answer in 1935 when Social Security was created, and it’s the question we have to answer today. Nothing an actuary says is going to get you out of having to answer it for yourself.

It’s not “welfare.” Social security is money meant to be returned to those who paid in during their time paying taxes, etc into the system. This “welfare” misnomer is important as it is created by those who stole the money in the fund to pay for other projects they deemed worthwhile. Classic politicization of a fund who’s inception would have never occurred if they did not piecemeal mold into what it is now. FDR introduced (fica) under the guise it was voluntary, returns wouldn’t be taxed, and the money paid in would be deductible. This is merely a sampling of what has become the boondoggle that is now social security.

De,

The false notion that Social Security benefits have ever been “set aside” or “lockboxed” is one of the biggest political cons perpetuated on the American public. Apart from a brief period just after its inception, American workers have not been “paying in” to anything other than the general treasury fund of the United States with their SS taxes and the Social Security benefits received by recipients are nothing other than a welfare program for mainly old people. The same is true of Medicare. I really wish people would stop thinking their SS taxes are somehow reserved to grow for their benefit but I have to admit it’s been an effective political tool to stop people from realizing it’s just a non-progresive tax on employment.

Also, the long term fiscal gap crisis IS real and ignoring it will only mean reduced GDP growth and burden future generations with reduced benefits or increased taxes.

SS funding needs to be addressed sooner rather than later so less extreme options have an opportunity to work before the trust fund is depleted. Your acidic rhetoric aimed at all things conservative would be better spent on creating productive dialogue about issues that impact most of us. Increasing the national debt by trillions of dollars will further devalue the US dollar and set the stage for the Chinese yuan to become the worldwide medium of exchange. There are huge ripples created by the bolder that you want to push down the hill.

Anthony,

I don’t see any conflict between your comment and what I wrote (except your concerns about the PH level of my rhetoric). We are short $186 billion a year over the next 75 years; we can either reduce spending by $186 billion per year, increase taxes by $186 billion per year, or print $186 billion per year in greenbacks. The point is simple: that $186 billion per year shortfall has nothing to do with Social Security’s funding mechanism.

Let me put it another way: the balance in the Social Security trust fund can only ever do 3 things in a given year: it can increase, it can remain the same, or it can decrease. If it increases every year, then our payroll taxes are unnecessarily high and should be reduced. If it stays the same every year, then payroll taxes are precisely covering our payments, and the trust fund is unnecessary. If it falls every year, it will eventually be depleted. But why is only the third case treated as a “crisis” that has to be urgently addressed? FICA taxes are flat and regressive (due to the income cap), and if you think debt is bad for whatever reason then the Social Security trust funds holding onto trillions of unnecessary Treasury bonds must be bad as well.

Ideally, I would simply bring Social Security benefits entirely on budget and have Congress appropriate them each year, the same way they handle every other budgetary issue. Failing that, issuing the $14 trillion in necessary bonds and depositing them in the trust funds would achieve the same goal: making Congress deal directly with taxes and spending instead of bankshot politics around trust fund accounting.

Note that this doesn’t necessarily mean tax increases and benefit cuts: if, like Japan, we remain in a below-target inflationary environment for decades we may decide that tax cuts or benefit increases are more appropriate! But, again, absolutely none of this has anything to do with Social Security’s funding mechanism, and we should break the link between FICA taxes and old age benefits as soon as possible.

—Indy