There has been a fair amount of confusion and chaos around changes made to the taxation of unemployment compensation in the American Rescue Plan, so as I’m finishing up preparing my own 2020 taxes, I want to draw readers’ attention to one very important and one very minor consideration when reporting unemployment insurance benefits received in 2020.

What’s the deal with taxable unemployment insurance?

Since the 1987 tax year, payments received from a state unemployment insurance program have been included in taxable income at the federal level. Since most states use federal income as the basis for their own income tax systems, that’s meant those benefits also flow through to state income tax returns.

There are “economic” arguments for and against taxing unemployment compensation, usually along the incoherent lines of whether untaxed unemployment benefits “discourage work” or whether taxed benefits “punish people who need the most help.” My controversial view is that all income should be taxed at the same progressive rates, and poverty should be addressed by increasing incomes, not creating kaleidoscopingly complex tax brackets for each unique kind of income.

The most important point, however, is that the taxation of unemployment benefits has never really mattered. That’s for three reasons:

- almost no one receives unemployment compensation, due to strict qualification and work-search requirements;

- unemployment benefits are very low (ranging from a maximum weekly benefit of $235 in Mississippi to $823 in Massachusetts);

- and unemployment benefits are extremely time-limited.

Until March, 2020, in other words, the taxation of unemployment benefits was mechanically irrelevant: nobody received enough in benefits to pay much in taxes, so recipients didn’t care, and the people who did receive benefits were so politically powerless they didn’t have any way to make the government care about their well-being.

During the pandemic, each of these reasons was comprehensively obliterated. Millions of people were pulled onto the unemployment rolls for the first time through new programs like Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, benefit amounts were aggressively topped up with federal funds, and time limits were increased from 26 to as many as 79 weeks, depending on the specific set of programs you were eligible for.

That meant for the first time, middle class workers found themselves on the hook for thousands of dollars in state and federal taxes they hadn’t budgeted for, and unlike traditional unemployment insurance beneficiaries, middle class workers vote.

Needless to say, a solution was quickly found.

The 2020 unemployment compensation tax exclusion

The solution was as crude as it was quick. In the American Rescue Plan Act, Congress simply excluded $10,200 in 2020 unemployment compensation per worker from taxable income. Unfortunately, the act was passed in March, long after forms and instructions were finalized and people had started filing their tax returns.

The IRS responded to this crisis in two distinct ways. First, it told people who had already filed their taxes not to file an amended return unless the exclusion would affect their eligibility for a different tax benefit (like the Earned Income Credit, Child Tax Credit, or Retirement Savings Contribution Credit). Instead, the IRS would itself calculate the exclusion and refund the difference in taxes owed.

It would be difficult to overstate how absurd this is. On a joint return, for instance, since unemployment compensation is reported jointly but the exclusion is per recipient, the IRS would have no way of determining whether one or both spouses had benefits exceeding $10,200 without manually consulting the 1099-G forms submitted by each state’s unemployment insurance office for each beneficiary. The IRS seems to believe they will be able to handle this administrative burden; on the contrary, I suspect this will produce a huge windfall for early joint filers where only one spouse received unemployment compensation, since I don’t think the IRS will ultimately have any choice but to exclude the full $20,400 from their reported benefits.

For those who had not yet filed their 2020 tax return, the solution was simpler, but does require some attention to detail. Unemployment compensation, like most non-W2 income, is now reported on Schedule 1 of Form 1040, on line 7. You might think that this is the number you need to adjust by up to $10,200 per unemployment compensation recipient. But that’s wrong, and the updated IRS instructions are crystal clear: “You should receive a Form 1099-G showing in box 1 the total unemployment compensation paid to you in 2020. Report this amount on line 7.”

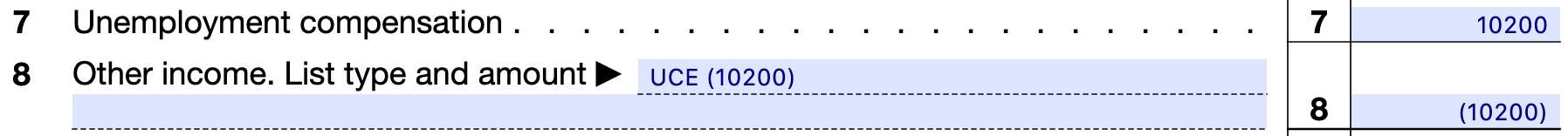

The exclusion is instead reported on line 8, “Other income,” as a negative amount. Then on “the dotted line next to Schedule 1, line 8, enter “UCE” and show the amount of unemployment compensation exclusion in parentheses on the dotted line,” so Schedule 1 of your return might look like this, depending on your tax software:

The paid family leave exclusion

For most people receiving unemployment compensation, that’s all you need to know. However, while reading the updated instructions I stumbled across a provision I’d never had any reason to be aware of: the paid family leave exclusion. The instructions for line 7 of Form 1040 Schedule 1 state:

“If you made contributions to a governmental unemployment compensation program or to a governmental paid family leave program and you aren’t itemizing deductions, reduce the amount you report on line 7 by those contributions.”

This is, to be clear, not a new provision of the American Rescue Plan; it was included in the original instructions for Form 1040 Schedule 1, and has been there for years (I’m still trying to figure out the precise origin of the provision, but it’s already there in 2016). The provision is important to be aware of, however, if you live in a state or the District of Columbia that allows sole proprietors to opt into paid family and medical leave programs.

The important thing to note here is that your paid family leave premia are treated in an opposite manner from the unemployment compensation exclusion: they are deducted directly against your unemployment compensation on line 7, not added as a negative value on line 8.

I assume the logic of this provision is that the premia paid for family leave insurance form a kind of “cost basis” of your coverage, so it would “unfair” to tax the “same money” “twice,” once when it “went into” the insurance program and a second time when it “came out.” That’s obviously bordering on the absurd, but it’s the way tax accountants and lobbyists think so it’s not terribly surprising they managed to smuggle it into law at some point.

If I’m reading that correctly, anyone in a state that has a paid family leave tax (NY, MA, etc) and received Unemployment, should also be able to deduct their contributions to that program from their Unemployment income.

This is moot if you received less than $10,200, but if you received more and/or make more than the $150k cutoff and don’t qualify for the Covid deduction, this does seem to come into play.

Note: I am not an accountant or lawyer, merely a layperson who likes fine print. I don’t know if my conjecture is correct.