Over the last year or so, I’ve read 20-30 books on investing, including short handbooks like The Index Card and somewhat more technical volumes like Jack Bogle’s Common Sense on Mutual Funds.

The thing virtually every book I’ve read on investing has in common is a recommendation that part of a portfolio be invested in bonds, and it took me a long time to understand why.

I finally did come to a few conclusions on this score, which I shared in this modestly interesting thread on the Saverocity Forum.

I’d like to take a slightly different approach to the same question, through the prism of some financial independence bloggers who are kind enough to share their actual investment portfolios online (or at least what they claim to be their actual investment portfolios). These aren’t bloggers I necessarily follow myself, but are rather bloggers who seem to have a general attitude towards investing that reflects mine: invest as much as possible in funds that cost as little as possible.

The White Coat Investor

Here’s the latest investment portfolio shared by the White Coat Investor blog:

- 75% Stock

- 50% US Stock

- Total US Stock Market 17.5%

- Extended Market 10%

- Microcaps 5%

- Large Value 5%

- Small Value 5%

- REITs 7.5%

- 25% International Stock

- Developed Markets 15%

- Small International 5%

- Emerging Markets 5%

- 25% Bonds

- Nominal Bonds (G Fund) 12.5%

- TIPS 12.5%

Physician on FIRE

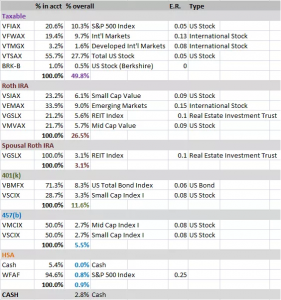

Here’s the latest investment portfolio shared by Physician on FIRE:

JL Collins

I’m a bit confused by how JL Collins describes his holdings, but I think he claims to be currently holding:

- 75%-80% VTSAX (Total US Stock Market)

- 25% VBTLX (Total US Bond Market)

- 5% “cash”

What benefits might diversifying investments conceivably provide?

If you happen to be a fan of these bloggers, trust me when I say I’m not trying to “criticize” these investment decisions. In an era of comprehensive historical market data and cheap or free backtesting data, I’m sure these portfolios have a higher (lower?) Sharpe ratio (or whatever) than my portfolio, and if that’s what you want then you can build such a portfolio yourself, or copy one of theirs.

But unless you know why you’re constructing your portfolio in the way you are, it seems to me vanishingly unlikely such a portfolio is the straightest path towards achieving your investment goals.

Of course, there’s no sense in talking about “diversifying” a portfolio unless you have a portfolio in the first place, so I’ll use as a “baseline” portfolio the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund, VTSAX, a fund that all three of the bloggers above use as their largest single holding. Why might a well-informed investor/blogger deviate from that portfolio?

- The belief that another asset class will provide a higher return on investment. This appears to be the logic behind the White Coat Investor and Physician on FIRE portfolios, with their addition of small-cap, mid-cap, and value funds to the core VTSAX holding. The investors appears to believe that such funds will generate higher returns than the market-cap-weighted total stock market index.

- The belief that an additional asset class will provide a more stable account balance. I don’t know why an investor would be interested, in general, in the stability of their account balance, but it is a fixture of financial writing that this is something people are, in fact, deeply interested in. This is how JL Collins explains his bond holdings: “Bonds provide income, tend to smooth out the rough ride of stocks and are a deflation hedge. Deflation is what the Fed is currently fighting so hard and it is what pulled the US into the Great Depression. Very scary” (emphasis his).

- Tax-loss harvesting. As Physician on FIRE explains, “Some of the complexity comes from tax loss harvesting, which results in me holding four funds in the taxable account, rather than two.” In other words, he does not believe that his added diversification will improve returns and he doesn’t believe it will lead to a more stable account balance, he diversifies solely for the purposes of not having substantially similar funds in his taxable account so he can trade them against one another for tax reasons.

If you want to diversify, first figure out why

After all the research I’ve done into investing, I was personally shocked to learn this, so don’t be surprised if it’s a shock to you as well: diversification doesn’t increase long-term returns. Diversification only increases long-term risk-adjusted returns, which is to say, returns adjusted for volatility in your nominal account balances. If you don’t care about your nominal account balances, diversification away from equities is a pure drag on your investment performance.

You may, in fact, be the kind of investor that cares deeply about your account balances, in which case, frankly, I don’t have any recommendation besides a heavy allocation to cash (here’s a great resource for high-interest checking accounts you might consider).

But if you’re a long-term investor who doesn’t care about your nominal account balances, you should diversify away from broad market indices only with caution and only when you have good reasons for doing so.

I must be missing something. Why are you advocating for ignoring nominal account balances? What is your end goal? If I understand correctly, the end goal for most people is to be able to safely sell and draw down their balances in retirement / those years when they are no longer contributing additional money to their investments. Doesn’t account balance matter for that stage? In fact, isn’t the account balance at the beginning that stage the most important metric?

(Seems like my other post disappeared. Let’s try again.)

I must be missing something. Why are you advocating for ignoring nominal account balance? What is your end goal? If I understand correctly, the classical end goal for long-term investing is the ability to safely sell and draw down your assets in retirement. In which case, shouldn’t the balance of your account at the time you start drawing it down be the most important metric?

Steve,

I found your other comment in spam, never fear!

I am not advocating for ignoring nominal account balances, I am personally ignoring nominal account balances because it is my intention never to sell my shares. My intention is to accumulate as many shares as possible in order to produce as much dividend income as possible in retirement.

—Indy

You already believe in diversification if you are using index funds. Depending on the time period, checking off more style boxes in your portfolio has outperformed a less diversified portfolio. That is, not just lower the risk (the measure of which is not universal), but an actual higher nominal return.

The old adage of “would you rather eat well or sleep well” is the driving force for most allocation decisions.

We live in unusual times, thirty year bull markets for bonds are unheard of in the longer term. This skews investing decisions in the same way that unusually low rates does. Thinking that a long term view saves you from having to consider price risk is foolish. There are at least two long terms during the 20th Century when your straightline returns were roughly break even!

The worst problem may be the misuse or misunderstanding of statistics in investing. The most common measure of risk is SD and is perfectly inadequate. It attempts to measure the risk of not realizing a projected return, which isn’t really what anybody is worried about. Try a Sortino Ratio for a better guess.

If you haven’t read O’Shaughnessy, he is worth reading. The use of rolling periods for return and risk measurement is a novel and (I believe) fruitful approach. He also uses a database that does not suffer from survivorship bias as so many sources do.

Dave,

Thanks for the recommendation, I’ll happily read anything.

The thing you say which cannot be true is that you can get a higher nominal return from a diversified portfolio than a single-fund portfolio. That cannot be true because your overall nominal return must be pulled up by those funds which outperform the portfolio’s average.

If you can pick the highest-performing fund in advance, you should just buy that fund and not buy the laggards in your portfolio.

—Indy

I’ve been investing since I was 13 and love reading Finance books/newsletters. Some are awful, most are marginal, a few are wonderful. Many are useful more for stock investing, as opposed to a passive approach, but still insightful.

Yes, mutual funds are like Gump’s box of chocolates. You never know what you are going to get. Since we are talking about funds, particularly index funds, we can ignore the measurement flaw of most studies. I did not mean to suggest that the weighted return of a portfolio of funds could be higher than the highest return of any constituent fund. The risk or volatility of returns could be lower, but that is not a goal for your portfolio (as I understand it.) It is precisely because returns are not perfectly predictable that there is an advantage to adding funds with different characteristics. Some correlations have increased so that traditional additions to, say, a large cap fund may not offer the boost in return that it once did.

Further, as I understand, in your particular portfolio you intend to leave principal intact, drawing only what income it produces. If that works, that gives you the advantage of ignoring price fluctuations. This is similar to a bond or bond portfolio which is all about the income. The price on any given day is unimportant to the recipient as long as there are no defaults. As long as dividends rise and the balance does as well, you are meeting your goal.

I just reread the last part if your post and it seens to me that you are really talking about asset allocation and not diversification. Whether you realize it or not, the holdings of equity funds all include a cash component. This is partly to account for net redemptions, some for fees and perhaps surprisingly because index funds may not hold all the components of the index they represent. It may not even be possible to exactly replicate an index. Some use futures and all struggle to match index returns when a component changes. Imagine having to swap out GM for DeVry, especially when GM was worth nearly nothing at the time! Not to say that the cash position is large or that adding more cash to your portfolio would absolutely increase returns. Time period is the key. If memory serves, the 1968-1982 or 1928-1954 periods demonstrate the long term value of having cash or bonds in a portfolio.

Sorry if I am rambling, can’t resist a good rabbit hole!

Dave,

I absolutely agree that returns are not predictable. The reason why I’m not personally interested in building a portfolio like the ones described in this post is that since I cannot predict the the future returns of the total stock market, and I cannot predict the future returns of any smaller slice of the stock market (small cap, mid cap, small cap value, REITs), in order to take advantage of the outperformance of any one market segment I have to be invested in every market segment, and since the sum of the performance of every market segment is the performance of the total stock market, I’ll therefore have a low-cost total stock market index side by side with 6-10 higher-cost market segment indices reproducing the total stock market! The outperformance of any one market segment will by definition be paired with one or more underperforming market segment (since together they all have to add up to the total market’s performance).

Now, it’s true that instead of reproducing the total stock market out of smaller segments you can reproduce only a few market segments. Both Physician on FIRE and White Coat Investor thus “tilt” their portfolios towards small cap and value stocks, presumably because they believe small cap and value stocks will outperform the total stock market. I think they might outperform the total stock market, and I think they might underperform the total stock market. I don’t see any reason to wager one way or the other with my actual investments, however (I have separate money I use to gamble on the market, but I don’t include that in my investments and I don’t compare the relative performance of my gambling versus my investing).

Ultimately, the reason I don’t use such portfolios for myself is due to their fixed % allocations within the portfolio, since such allocations generate regular buying and selling activity (selling winners to bring down their portfolio share, buying losers to bring them back up to portfolio share). That kind of market timing seems vanishingly unlikely to lead to outperformance (though it may lead to better risk-adjusted performance — again, I don’t care about risk-adjusted performance so that doesn’t matter to me).

—Indy

Now that I have confirmed this ability AND have actually read the post, I tend to agree you seem to be talking more about asset allocation and not necessarily diversification. All that being said, I’ve been debating my 0% allocation in bonds lately, due to having kids or what not. Still probably going to gamble on equities for their futures though. But I’ve considered it for the first time in years.

Just out of curiosity what does your portfolio/asset allocation consist of? I’m toward the mindset these days to be 100% in stocks but read different ideas about much to be in international stocks vs US stocks etc and would be interested to hear your thoughts and opinions.

Testing my ability to bold

Mr. Money Mustache FTW (associate of JLCollins)

It sounds like you’ve made the assumption you will NEVER sell or re-balance. If you sought more *flexibility* to respond to market conditions (or, life), you might find yourself wanting more cash, bonds, securities. Not indulging in that flexibility sounds like a perfectly legitimate strategy. This premise of keeping money off the table is often a mistake, and people lose potential earnings “waiting for the crash.”

You may be right in your discipline and resisting the urge to respond to markets, or to timing.

That said, I also had the same viewpoint as you in my 20s, but found that 5 years into investing heavy in my “don’t touch until 65” account, the market crashed and simultaneously (for completely orthogonal reasons), I wanted to go on a mini-retirement. Perhaps you’ll never be in such a situation, but one premise you’re making appears to be that you’ll continue to contribute. I’m not sure the math on my situation, but I know it wasn’t good for my long-term financial health. But neither was my job. Be warned — you may always encounter situations you didn’t anticipate, and you may want more flexibility – including to do the forbidden draw down.