[edit 6/13/17: I’ve been convinced that employee “elective” and employer “non-elective” solo 401(k) contributions can be made with the same money, so have slightly updated the values below to reflect that employer contributions don’t have to be made with what’s “left” after deducting up to $18,000 in elective employee contributions. I’ll have a post soon exploring this issue in more detail.]

Everybody gets a song stuck in their brain sometimes, the only proven cure for which is putting on the song at maximum volume and belting it out in your underwear.

Along with songs, I also get personal finance calculations stuck in my mind that I can only stop thinking about once I work out the math and blog about it.

Recently I’ve been thinking about what should be, but isn’t, a trivially simple question: what is the marginal federal tax rate on a sole proprietor’s income?

For each calculation I’ll be assuming the sole proprietor is filing as a single taxpayer and has no other taxable income. Additionally, all retirement contributions will be made pre-tax. In other words, this is a taxpayer whose only objective is to pay as little as possible in current-year federal taxes. Adjusting these rates for your own situation is an exercise left for the reader.

Finally, these rates are calculated on the net business income reported on line 48 of Schedule C. Don’t confuse that with “earned income” or “adjusted gross income.” These are just the marginal tax rates paid on your actual profits from your actual business, if it’s your only source of income.

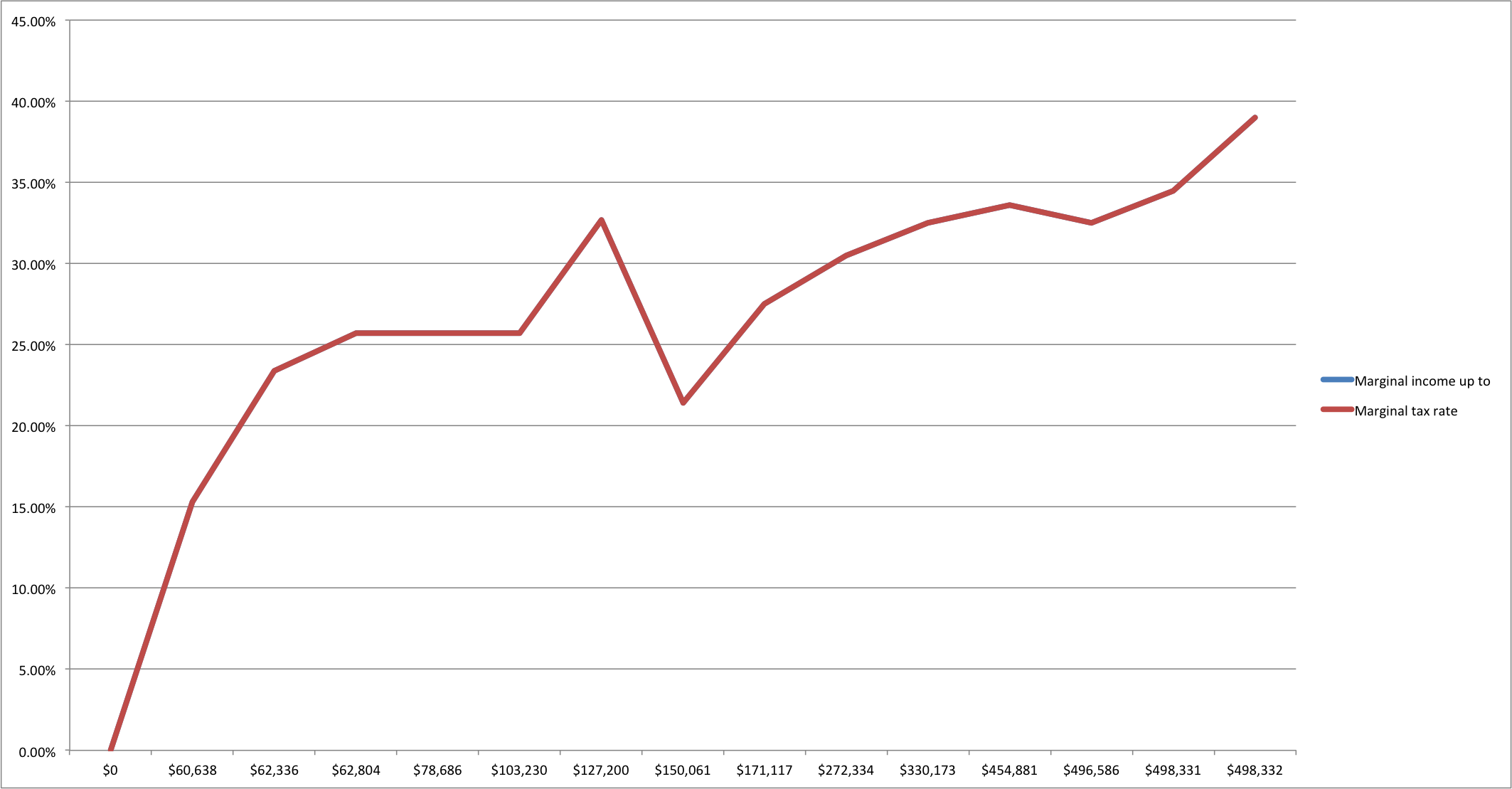

Marginal federal tax rates on a sole proprietor’s income

- 15.3% for income up to $54,142 $60,638. At $60,638 in self-employment income, you’ll owe $9,277 in self-employment tax. Reducing your self-employment income by half that amount, $4,615, will leave you with $56,000 in earned income. A $5,500 traditional IRA contribution, $18,000 pre-tax “employee” solo 401(k) contribution, and $14,000 “employer” solo 401(k) contribution will reduce your adjusted gross income to $18,500. After deducting your $4,050 exemption and $6,300 standard deduction, you’ll be left with taxable income of $8,150 and income tax due of $818 which will be fully offset by your retirement savings contribution credit of $818.

- 41,800% on the next dollar or two of income. It’s actually a bit tough to calculate the precise point when your adjusted gross income will tip over to $18,501 due to the multiple decimal places involved, but at that point, you’ll owe the same $818 in taxes but your retirement savings contribution credit will drop to $400. You’ll pay $418 in taxes on a dollar or two of income, leaving you with a marginal tax rate of 41,800% (or 20,900% if you want to spread it over two dollars of income).

- 23.4% for income up to $62,336. It’s important here to note that, having maxed out your $18,000 in straight employee 401(k) contributions, you can only contribute one out of every four dollars as an “employer” contribution to your solo 401(k). That means the $1,500 in adjusted gross income up to the next retirement savings contribution credit threshold is actually $2,000, which has to be adjusted for the usual and obnoxious 92.35% adjustment, for a total of $2,165 in net self-employment income you can earn before the next threshold. In this band, every $72 in net self-employment income results in an additional $5 in federal income tax and $11 in self-employment tax ($72 reduced by 7.65%, then by 25%, results in $50 in adjusted gross income).

- 25.7% up to $62,804. In this band, every $72 in net self-employment income results in roughly an additional $7.50 in federal income tax and $11 in self-employment tax.

- 20,000% on the next dollar or two of income. As above, moving from the 20% retirement savings contribution credit band to the 10% band reduces your credit by $200.

- 25.7% up to $78,686. Here you’re still in the 15% income tax bracket and receiving a $200 retirement savings contribution credit.

- 20,000% on the next dollar or two of income. This is the final phaseout of the retirement savings contribution credit. Earn a buck, pay $200.

- 25.7% up to $103,230. At $103,230, your adjusted gross income will total $48,000, leaving you with $37,650, the top of the 15% income tax rate.

- 32.7% up to $127,200. In 2017, $127,200 in net self-employment income will max out the Social Security component of your self-employment tax (finally!), and leave you with $54,252 in taxable income, squarely in the middle of the 25% income tax bracket.

Let’s take a break here to talk about the next two things that are going to happen. First, the amount by which your net self-employment income will be adjusted is going to change. Before we’d been using a variable 7.65% adjustment to account for half the self-employment tax, which is figured as 15.3% of your net self-employment income up to $127,200. Now we’re going to use a fixed $9,730 adjustment, which is half of the 15.3% levied on the first $127,200, plus a variable adjustment of 1.45% on the amount over $127,200, which is half the self-employment tax levied on amounts in excess of $127,200. So $128,000 in self-employment income will be reduced first by $9,730, then a second time by $11.60 (1.45% of $800). That’s going to bring down your marginal tax rate, a lot. We can still contribute 25% of what’s left as an employer contribution to our solo 401(k). In this case, that employer contribution is $29,564.

That brings us to the second thing that’s going to happen: the ability to make employer contributions to your solo 401(k) will end when total employer contributions total $35,000. We’ll have $35,000 in employer contributions when our total self-employment income is $150,061. Reduce that amount by $9,730 and 1.45% of the amount in excess of $127,200 ($331) and we’ll have $140,000. The quarter of the remaining amount is your maximum employer non-elective 401(k) contribution: $35,000. Just as lower self-employment taxes lower your marginal tax rate, losing the ability to contribute a quarter of what’s left will have the effect of raising your marginal tax rate.

One final note here: Matt and I have disagreed about whether you can contribute the same dollar twice: once as an employee and once as an employer. I think you can only contribute the same dollar once, which is why I have assumed all employer contributions are made from what’s left after the maximum employee contribution is made. If anyone has a definitive answer to this question, I’m all ears. I’ve been convinced that Matt is right about this.

Ok, back to business.

- 21.4% up to $150,061. Between $127,200 and $150,061, you’ll pay 2.9% in self-employment tax on each dollar of net self-employment income, then 25% of 75% of 98.55% of what’s left.

- 27.5% up to $171,117. In this band you’re paying the lower self-employment tax rate of 2.9% on each marginal dollar of self-employment income, but now have to pay 25% of the entire 98.55%: you’re no longer able to make additional employer contributions to your solo 401(k).

- 30.5% up to $272,334. Here you’ll pay 2.9% in self-employment tax on each dollar, then 28% of the remaining 98.55%.

- 32.5% up to $330,173. At $330,173 in net self-employment income, you’ll have an adjusted gross income of $259,000.

At this point, the personal exemption starts to phase out, until it’s eliminated completely at an AGI of $381,900 (net self-employment income of $454,881).

- 33.6% up to $454,881. For each $2,500 you earn, you’ll pay 33% on 98.55% of your net self-employment income plus 33% on 2% of $4,050 (no, I’m not kidding).

- 32.5% up to $496,586. Now that the personal exemption has been completely phased out your marginal tax rate drops back down to 33% of 98.55% of your net self-employment income.

- 34.5% up to $498,331.

- 39% on all additional marginal dollars of net self-employment income.

Conclusion

Now that my brainworm has been well and truly exterminated, there’s only one thing to do to reward folks who have made it all the way to the end, and that’s show exactly the same data in chart form:

One hell of a way to run a railroad.

A calculus problem! Excellent example of why tax code needs major revision. Wouldn’t you rather pay a bit of tax, and not have to worry about this?

I have a simpler system on slightly more income that our blogger, but sole proprietor also. Earn enough to meet my needs. make max contributions to anything pretax I can, deduct everything I can (travel, home office etc), Calculate my bottom line and give worthy causes whatever is necessary to reach 0 taxible income. Don’t feed the coffers of war, do good in the world, and feel good at the end of the day. I work hard at it. legal and accountable.

mom,

Have you ever had to deal with the Alternate Minimum Tax? Those calculations are a bridge too far, even for your humble blogger.

—Indy

AMT is the only way to keep you rich people paying your fair share of the taxes.

I am not smart enough to even think about AMT. not rich enough to have it affect me. I file without considering. I find IRS very gracious about checking my taxes. There have been couple years with corrections They usually get it right. I say thank you and write the check. Or thank you and put it in bank. Much easier and cheaper than hiring an accountant

The good news is that the AMT doesnt just affect “rich” people. Its lack of indexing to inflation has left it to eff with ppl who arent even close to being rich

That sounds wonderful, but charitable deductions are limited to a percentage of income. I don’t ever take deductions for gifts in kind anymore since I can never deduct them.

Could you make the chart bigger? I can’t read either of the axes

Fiby,

I can try! I am VERY bad at Excel.

—Indy

Fiby,

Hope that helps!

—Indy

Are you sure you can contribute to both a 401k and an IRA?

Absolutely. Though you need to be mindful of the salary limits for the IRAs, the 401(k) aspect is irrelevant though.

There is a conflict between Model 5305 SEP IRA and Individual 401(k)

EDIT It might be confusing to read that the 401(k) is irrelevant. It does come into play with regard to salary limitation for deducting a Traditional IRA, but the 401(k) itself doesn’t prevent you from contributing to an IRA.

If you think this equation is screwed up, wait until you and your spouse both have jobs, married filing jointly, and running a side gig selling on Amazon.

Somehow $20K of profits became a $10K tax liability. Ugh.

whos gonna pay for those with their hand out? Not people with no income.

Pointless statement. We all have our hand out.

Regarding your final comment/disagreement with Matt about whether you have subtract the “employee” contribution before figuring the “employer” contribution (or vice versa) –

Here is the example from the IRS website https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/one-participant-401k-plans that shows that you do not have to do that:

“Example: Ben, age 51, earned $50,000 in W-2 wages from his S Corporation in 2016. He deferred $18,000 in regular elective deferrals plus $6,000 in catch-up contributions to the 401(k) plan. His business contributed 25% of his compensation to the plan, $12,500. Total contributions to the plan for 2016 were $36,500. This is the maximum that can be contributed to the plan for Ben for 2016.”

To summarize – your contribution limits as an employee are $18K (or $24K if age 50+) and that is per person. The employer (also you in this case) can contribute 25% of your compensation (closer to 20% if you are not your own W-2 employee) from the original earned amount, not the amount after the employee deferral.

Also please note – I’m just a dumb doc who moonlights, but my accountant and the IRS both say this is legit. I do not have an S-corp; all my moonlighting is non-W-2. I figure my “employer” contribution based on my total after payroll taxes, expense deductions, etc – but not after my “employee” deferral Check with your qualified tax advisor. Let me know if I’m misunderstanding you, or if you are hearing differently from others.

Peace.

ArmyDoc,

You understood our disagreement perfectly, and thank you for the link, that is indeed the precise situation I’m describing!

The reason I believed you couldn’t contribute the same dollar twice is if you consider the case of someone making $19,941 in schedule C net income: they’ll have $18,000 in income after deducting half the self-employment tax, and thus be able to contribute $18,000 as an employee. If you don’t have to deduct those contributions first, then the person would also be able to make $4,500 in employer contributions. Since employer and employee contributions for a sole proprietor are both deducted on line 28 of form 1040, you would be able to deduct $22,500 against $19,941 in self-employment income.

That may be the case! No one has ever accused the IRS of making sense. But it would be extremely odd.

—Indy

Indy –

I’m sure there are nuances I don’t get! The example definitely does not cover your exact situation now that you’ve laid it out for me. Hope some smart accountant will chime in with a definitive answer !