Finance, like many professions stocked with men trying to impress each other, has accumulated a plethora of cliches like barnacles on the hull of a ship. Among the hoariest is the admonition, “don’t buy the dividend.” Since I, personally, love dividend-paying stocks, not because of their “outperformance” or their “value” but simply because they pay dividends, I decided to check whether or not “buying the dividend” really is a bad idea.

Why buying the dividend shouldn’t work

In a stock market that has already perfectly priced in every participant’s expectations of the future, you might expect share prices to be stable as well. Not so! In fact, in such a market each day share prices should increase by the discounted value of their dividend payments until the final day when owners are eligible to receive that dividend. The next day (the ex-dividend date), the share price should fall by the amount of the dividend, before starting to gradually rise up until the next eligible payment date.

This is, in fact, what you see in mutual funds whose net asset value is calculated at the end of each day. The mutual fund’s value is the sum of the shares it holds and the cash dividends it has accumulated for distribution; upon distribution, the cash value falls to (or near to) zero and the net asset value of the fund likewise falls. Shareholders receive the difference in cash, which they can reinvest or keep, thus leaving the account value unchanged.

Why buying the dividend might work

One reason why buying the dividend might work is that, in general, stocks are very volatile but tend to go up in value over time. Let’s take a stylized example: there are roughly 63 trading days in each quarter. A stock that pays a dividend of $1 per quarter, according to the logic above, should rise in value about 1.6 cents per trading day, before falling $1 on the ex-dividend date. If the stock typically moves $2 up or down on any given trading day, but moves up 60% of the time and down 40% of the time, then 40% of the time the stock will drop $3 on the ex-dividend date (the normal volatility of $2 plus the decreased intrinsic value of $1) while 60% of the time the stock will similarly gain $1. Since in either case you get to keep the $1 dividend, your expected value should be $0.40 per share.

Why it would be nice if buying the dividend worked

The reason why it’s worth asking whether buying the dividend works is that it would be a way of capturing the dividend yield of a stock with very little exposure to its underlying risk — just four days per year in the case of a stock that pays dividends quarterly. In an extreme case, if a stock’s price was completely indifferent to its dividend payout schedule then the stylized case above would have an expected value not of $0.40 per share, but rather $1.40 per share: the $1 dividend plus the $0.40 expected value of a single day’s ownership.

You could quickly jump from one stock to another and use the same money over and over again to buy as many dividends as possible each quarter, or you could put the money in a high-interest savings account the 246 trading days of the year your stock of choice isn’t about to go ex-dividend.

But buying the dividend doesn’t work

Anyway, since I take money literally, I decided to see whether buying the dividend does or doesn’t work. My methodology was simple, since a purely mechanical trading strategy like this needs purely mechanical rules:

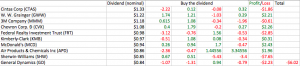

- I took the 52 companies on this list of S&P 500 “Dividend Aristocrats.”

- I sorted them by their nominal dividend payout, on the grounds that the highest nominal payouts will appear most clearly in the stocks’ historical price data.

- For the top ten stocks ranked by nominal dividend payout, I looked at the last 4 dividend payouts. This usually meant going back 4 quarters, but in the case of annual or biannual dividend payouts I looked back further.

- For each of the top ten stocks, I looked at the opening price on the last day investors were eligible for the dividend, and the opening price on the ex-dividend date.

To implement this strategy, you would place a market buy order before the market opened the day before the ex-dividend date, then a market sell order before the market opened on the ex-dividend date. You’d be exposed to one day of market volatility, either positive or negative, and receive each company’s dividend. Here’s what I found:

This is just about as close to a random walk as you’re gonna get in the real world:

- 5 of the 10 companies showed a profit buying the dividend and 5 showed a loss.

- 21 of the 40 datapoints showed a profit and 19 showed a loss.

- 3 of the 10 companies showed a profit on 75% of datapoints.

- 5 of the 10 companies showed a profit on 50% of datapoints.

- 2 of the 10 companies showed a profit on 25% of datapoints.

- Interesting, none of the companies showed a profit on all four of their datapoints.

- On the other hand, the entire loss of the strategy is accounted for by a single company: Sherwin-Williams. With that company’s dividends excluded, the strategy flips to a positive $1.63 return!

Conclusion

I think the best way to think of this strategy is as a negative-expected-value gamble but with only a modest house edge. To take an analogy from craps, it’s like making a come bet on every roll once a point has been established: you’ll lose money over the course of an evening, but you’ll win a little bit back every time you seven out, which helps take the sting off.

My goal is to increase value of portfolio with as little dividend as possible (don’t want to pay taxes.). I have learned that market fluctuations, whether on one stock or entire group, are based on so many factors that we folks on street can’t begin to know of base investments on them.

What about the buying dividend aristocrats with the lowest price to dividend ratio, reinvesting dividends?

Still have to pay taxes, even if reinvest

Not if the dividend is paid out in stock instead of cash, without the option of a cash dividend.

Qualified dividends aren’t subject to income tax at all if you’re in the 10% or 15% tax bracket and they’re only taxed at 15% if you’re in the 15%-39.6% bracket. So if you make less than $38,000 a year you will pay $0 tax on those dividends. The best would be to earn less than $38k in strictly dividends with no other income and you will pay $0 on that dividend income.

http://www.investopedia.com/terms/q/qualifieddividend.asp

I transferred 100k into Fidelity exactly one year ago and bought 950 shares of AAPL at $105…mainly for the dividend.

I’m going to sell tomorrow (long term cap gain) and will clear $32k after tax.

So yea…I’m buying the dividend,

You’re buying the hype. Glad it worked out for you.

Let me just put this here for you to play with.

http://retrolyzer.com/

R,

Thanks, looks like a cool tool!

—Indy