One of the most important things you can learn as you study finance and investing is that the markets do not care about you. This is, on the one hand, terrific news: if the market cared about you, you might find it an angry and vengeful, rather than benign, master. The flip side is that your personal development as an investor has absolutely no effect on prices in the market.

It’s that second lesson that people have difficulty accepting, but is most valuable to learn well, if you’re able to.

There are lots of great investment strategies

Standardized databases of share prices and company financials make it trivial for professionals to identify strategies that, when applied to historical prices, outperform buying and holding a broad US market index fund over time.

My favorite example of these data-mining strategies is so-called “momentum” investing, which is supposedly based on the observation that asset classes that have recently increased in price tend to continue doing so while asset classes that have recently fallen in price likewise tend to continue falling.

When I make fun of this strategy its advocates get the mistaken impression that I think this observation is false. I think no such thing.

Another popular investment strategy is so-called “value” investing, which, depending on the level of complexity of the strategy, may involve buying assets taking into account their price, quality, leverage, or any number of other factors, based on the observation that, if properly selected, such assets tend to perform better over long periods of time.

This is a perfectly reasonable observation, and one that may prove to be true in the future as well, although it’s famously hard to make predictions, particularly about the future.

Different investment strategies produce price appreciation at different times

I was listening to an interview with Jack Bogle, who said something that didn’t seem like it could possibly be true: the Vanguard Value Index Fund (VIVAX) and Vanguard Growth Index Fund (VIGRX) have had identical performance since the funds began. The Value fund returned more in dividends than price appreciation, while the Growth fund returned more in price appreciation than dividends, but each experienced the same total return.

It turns out this isn’t quite literally true, but it’s darn close. Since inception on November 2, 1992, VIVAX has returned a cumulative 791.58% and VIGRX has returned a cumulative 721.96%. That’s pretty close for a 25-year investment horizon!

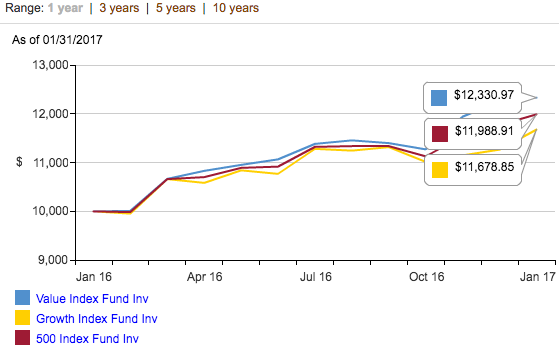

But now let’s look at the performance over shorter periods. In the past year, Value somewhat beat out Growth:

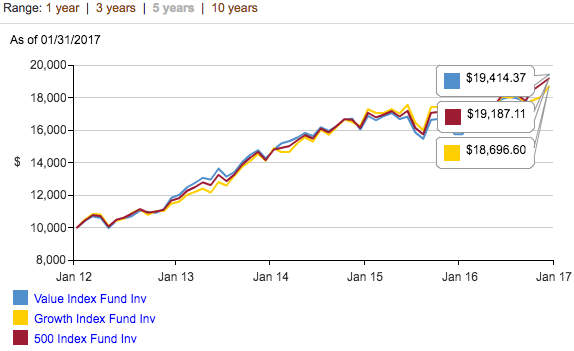

In the past 5 years, Value again has a small edge:

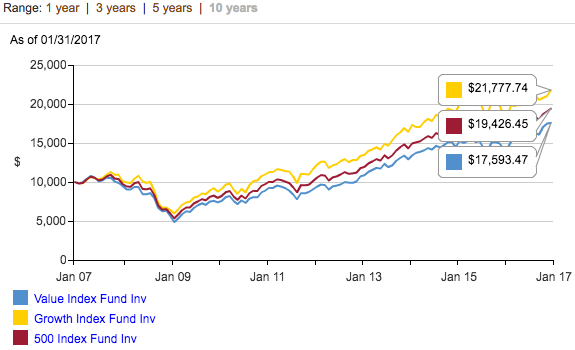

In the past 10 years, Growth has a large edge:

Keep in mind that we know that since inception, the funds have had virtually identical returns (yes, 0.5% over 25 years adds up, but it doesn’t add up THAT much):

![]()

So which performs better? It can’t be the case that “over 10-year time horizons Growth consistently outperforms Value but over 25-year time horizons Value consistently outperforms Growth,” because every 25-year time horizon consists of multiple overlapping 10-year time horizons.

What we can say for sure is that “over some time horizons one will outperform the other, but over very long time horizons the difference probably isn’t worth worrying about.”

Discovering a strategy is a big deal for you but the market doesn’t care

So we’ve established that there are a lot of different strategies, many of them work fine, but they work fine over different time horizons.

The problem is that you can’t personally implement a strategy until you, personally, find out about it. There are three possibilities for when you might find out about a strategy:

- at a random time, with an equal possibility of the strategy outperforming in the near future or underperforming in the near future;

- at a particularly auspicious time, with a higher probability of the strategy outperforming than underperforming in the near future;

- at a particularly inauspicious time, with a higher probability of the strategy underperforming.

It seems obvious to me that you are most likely to find out about a strategy at a particularly inauspicious time to begin implementing it, because the financial media spends an overwhelming majority of its bandwidth covering strategies that have worked in the most recent past, while reversion to the mean is the most powerful force in the financial universe.

Make changes to your investment strategy deliberately and implement them gradually

One solution to this problem of timing is to never make changes to your investment strategy.

That’s a pretty good plan!

But there really are genuinely bad investment strategies out there, so I don’t want to prejudge how good or bad your existing strategy might be. If it’s really bad, for example if it comes with high fees, high turnover, or both, then you should certainly not feel wedded to it for eternity. But the last thing you want to do is hop from one strategy to another just because you, personally, happened to find out about it.

So let’s say I’m a relatively new investor who knew he should invest with Vanguard, and after poking around their website discovered that over the past 25 years Value had slightly outperformed Growth, and therefore decided to make his regular weekly IRA contribution to VIVAX.

After a few years, imagine I stumbled across this blog post and discovered that what I thought was a secret to squeezing additional returns from my investment is just a historical artifact and there’s no reason to believe Value will enjoy that same 0.5% advantage over the next 25 years, and that really I should just be holding the Vanguard 500. What should I do?

My argument is that the worst thing I could do is instantly exchange my entire IRA balance from VIVAX to VFINX, since that is allowing the fact that I, personally, just found out about an investment strategy to influence my decision. But I made my discovery at a completely arbitrary time, and my Value investment is just as likely to outperform as underperform the Vanguard 500 over the next 5 or 10 years!

There are two perfectly reasonable things I could do, however:

- Change the investment of new money. I could make a switch in my automatic investments from investing in VIVAX to investing in VFINX, and simply let my Value investment ride. Maybe it will slightly outperform, maybe it will slightly underperform, but it will represent a relatively small amount of my final portfolio 10 or 20 years from now.

- Gradually shift my VIVAX investment over to VFINX. In addition to changing my automatic investment settings, I could set up an automatic exchange between Value and the Vanguard 500 in order to, over 1, 3, or 5 years, completely replace my Value shares with Vanguard 500 shares. This would allow me to possibly take advantage of any Value outperformance while, over time, correcting a relatively minor mistake.

The worse your initial investment decision, obviously the sooner you’ll benefit from correcting it, but the fact is most reasonable investment strategies work fine over long enough periods of time. If you find yourself in a hole, you should certainly stop digging, but if you find yourself jumping from one hole to another every 3 or 6 months, then your problem is, unfortunately, likely much more serious than your investment strategy.

*Standing ovation*

started using this Robin Hood. No commission at all!!

you can buy as little as one share at a time… Once I make a few hundred bucks I Sell and I’m never exposed to the market in any big way. Been cranking out over $1000 a month with less than 10 grand on the line

Even Berkshire Hathaway was a bad stumble for Warren Buffet back in the day. Had he put that money into a cash making machine instead, who knows what would have happened.

Case in point, we all make mistakes. As long as your long-term view and persistence keep working for you, hopefully you’ll have a few pesos to retire on.