As in my wont, I was browsing through depositaccounts.com to see if anything interesting was happening in the world of consumer-facing interest rates. I was surprised to see a few new borrowers at the top of the interest rate league table, with Merchants Bank of Indiana and Workers Credit Union offering 5.65% APY on 36-month certificates. The products used a term I hadn’t seen before: the highest interest rates are offered on “flex” certificates. Intrigued, I set out to learn more.

The consumer-facing yield curve is extremely inverted

In traditional finance, if short-term interest rates are expected to stay the same, then longer-term loans are expected to pay higher interest rates than shorter-term loans. If interest rates are expected to rise, then longer-term loans should pay much higher interest rates than shorter-term loans. If rates are expected to fall, then longer-term loans should pay the same or lower interest rates than shorter-term loans.

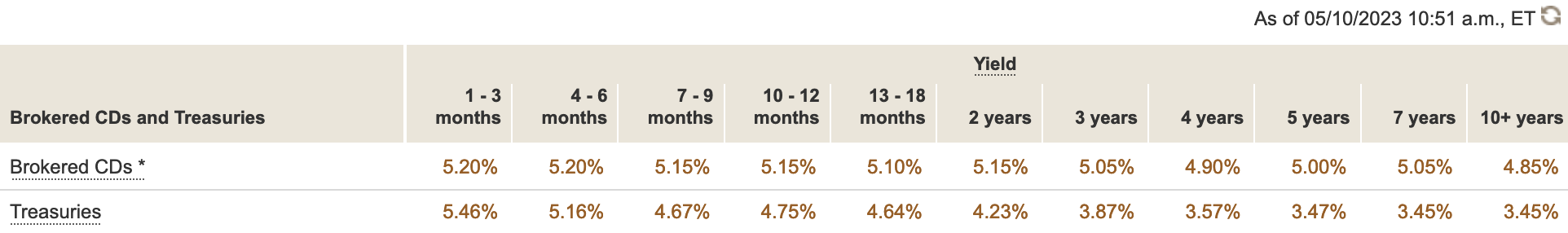

That second condition is referred to as an “inverted” yield curve, and is the situation we have been in essentially since the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates. I don’t like to talk about theory when the facts are readily accessible, so here’s an illustration of the current shape of the consumer-facing yield curve for US Treasuries taken this morning from Vanguard’s website:

As you can see, the 10-year yield is the same or lower than all the shorter-maturity Treauries — a classic inverted yield curve.

This creates an interesting conundrum for borrowers: how do you convince people to lend you money for the long term at a lower rate than they’re able to earn for the short term? To answer this precise question, adjustable rate loans were born.

The many genders of adjustable rate loans

Most people are familiar with adjustable rate loans in the context of mortgage debt. When a borrower takes out an adjustable-rate mortgage, they usually lock in a fixed interest rate for a certain number of years. After that period has elapsed, then the interest rate is adjusted at specified intervals based on the current value of the mortgage contract’s interest rate index.

Adjustable rate mortgages “protect” banks from the risk of rising interest rates since those higher rates are eventually reflected in payments and interest. In exchange, they come with lower rates or better terms than fixed-rate mortgages. If rates fall, then payments and interest on adjustable rate mortgages eventually fall as well, but that means people with adjustable-rate mortgages are less likely to pay off or refinance their loans early.

Another, less common form of adjustable rate loan is so-called “bump” rate certificates. With these instruments, a known interest rate is offered for the life of the certificate, but the customer has the option of a one-time increase in the interest rate from the time of the request until the certificate matures. Again, in exchange for protection against rising interest rates, the customer usually has to accept a lower guaranteed interest rate on their deposit.

Floating-rate certificates

Until this week I wasn’t familiar with what banks are calling “flex” rate certificates but which are best thought of as adjustable-rate or floating-rate loans. These products advertise a known starting interest rate and fixed term, but once the account is open the interest rate changes whenever its interest rate index does. I think these are pretty interesting products, but there are quite a few different pieces to keep track of.

- What is the term?

- What is the interest rate index?

- What is the premium or discount on the index?

- How often can the interest rate adjust?

- Is there a minimum or maximum interest rate?

We can see how these factors work using the two example banks above.

Merchants Bank of Indiana Flex Index CD

Merchants Bank of Indiana (MBI) offers 12-month, 24-month, and 36-month Flex Index CD’s. The minimum deposit for all three terms is $1,000.

For all three terms, the interest rate is calculated based on the Prime Rate, currently 8.25%.

For all three terms, the interest rate is the Prime Rate minus 2.75%, for an interest rate of 5.5% and an annual percentage yield of 5.65%.

MBI states that “[y]our interest rate on your account may change at any time based on changes in the index.”

The minimum interest rate is 0%, and there is no maximum interest rate.

Workers Credit Union Flex Rate CD

Workers Credit Union (WCU) offers 6-month, 1-year, 24-month, and 36-month Flex Rate CD’s. The minimum deposit for all four terms is $500.

For all four terms, the interest rate is calculated based on the Federal Funds Target Rate, currently 5.25%.

The adjustment to the Federal Funds Target Rate depends on the CD term:

- 6 months: minus 0.5%

- 1 year: minus 0.25%

- 24 months: no adjustment

- 36 months: plus 0.25%.

WCU states that “[w]hen the Fed Funds rate changes, the credit union will make the new rate effective on your account within or on the second business day after the announcement.”

WCU does not specify a minimum or maximum interest rate.

Floating-rate certificates are a low-stakes bet on high and stable interest rates

With the above context in mind, the basic value proposition of floating rate certificates becomes clear. With interest rates currently higher than they have been in over a decade, money is once again extremely valuable to banks, because they can finally lend it out at a profit again. Further, a stable supply of deposits is more valuable than a short-term one, both for regulatory purposes and to make their assets and liabilities more predictable. Sensibly, banks are therefore once again willing to pay civilians to borrow their cash in the form of deposits.

What keeps the bankers up at night is the prospect of lower rates on the horizon. The market’s inverted yield curve is the result of millions of individual decisions reflecting that fear: every loan longer than a year has baked into it a bet that interest rates will be substantially lower in the future than they currently are. For borrowers like MBI and WCU, a floating-rate certificate is a way of transferring that interest rate risk to their depositors: if their index rate goes down, they’ll owe less in interest. If rates go up, they’ll pay more in interest, but be able to lend the money out at higher future rates.

This can be a reasonable proposition for customers as well. If rates fall, it’s true the interest they earn on their deposit falls. But the short-term interest rates available elsewhere will fall as well, so this isn’t as bad as it sounds. Consider, for example, a 36-month CD offering the highest fixed interest rate I could find, the 4.75% (4.85% APY) offered by Summit Credit Union.

For the interest rate on one of the 36-month floating rate certificates discussed above to fall to 4.75%, their indices would need to drop 0.75 percentage points. I think there’s a pretty good chance that interest rates will fall at least 0.75% sometime in the next 36 months, but that is not nearly enough information to know whether you will earn more interest on a floating rate or fixed rate certificate.

The answer to that question depends on how soon, how fast, and how low interest rates fall. If interest rates fall 0.75% immediately and stay there, then you will have lost nothing, since that’s what fixed-rate certificates currently pay. If interest rates fall in 35 months, you’ll similarly have lost only a month of interest at today’s rate. There is of course a breakeven point, where low enough interest rates, soon enough, will turn the floating rate certificate into a loss compared to a fixed rate certificate.

But even this is not quite as bad as it sounds, since most CD’s allow you to cash out your deposit early at the cost of some amount of accrued interest. When the next global economic crisis strikes, you can withdraw and redeploy your money elsewhere.

Conclusion

The point of this post is not to provide publicity to MBI or WCU — I’m not here to sell anything. But by breaking down financial products you can see exactly what you’re getting and how much you’re paying for it. In the case of floating rate certificates, you’re accepting a premium on the current short-term interest rate in exchange for giving up the certainty of a fixed, albeit lower interest rate.

I have no idea if the premia being paid by MBI and WCU make that a fair exchange, partly because the right premium will vary from person to person. For example, if a retiree is planning to use the income from a certificate to pay for living expenses, then a fixed interest rate certificate gives them more near-term certainty about their interest income than a floating rate certificate.

On the other hand, if you’re still saving money and trying to construct a diversified portfolio, then floating rate certificates are a way to benefit if interest rates rise without risking your principal.

Likewise, if you are very certain of a pending financial crisis that will lead to another lost decade of 0% interest rates, then you should need a very high premium to accept a floating interest rate, while if you are confident in the stability and growth of the US economy over the next 3 years, then you should expect stable or rising interest rates and be willing to accept a smaller premium on current rates, or even a discount, to capture those rising rates in the future.

Leave a Reply