Recently, in The Forum, I was discussing the strengths and weaknesses of dollar cost averaging (DCA) vs lump sum investing. While many think of DCA as a powerful financial mechanism, there are two key flaws that arise from its implementation. The first is lazy money syndrome. DCA drips money into an investment over time. that means that by nature you have money out of the market, and by the time it gets in you have lost out on growth. The second issue is that after having lost out on the growth, you still are in a position where you are ‘all in’ with DCA, and if your assets are poorly structured then you are no better shape.

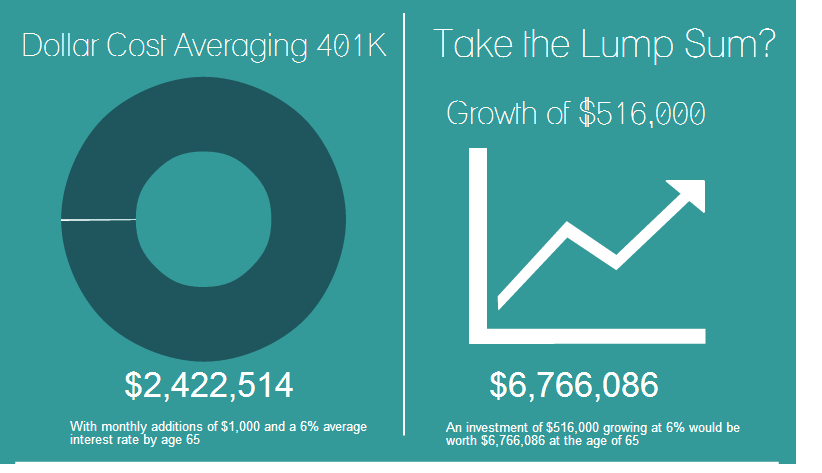

I know that dollar cost averaging has a lot of cheerleaders. However, it really breaks down when you consider the logic of it. Let’s look at the other time where DCA occurs- periodic investment strategy; such as paycheck deductions into a 401(k). As we know, taking a fixed sum every month, of perhaps $1000 from our paychecks and putting them into a 401(k) is one of the best ways to save. But what if there was an alternative? What if you could find a job that when they hired you out of college they offered to front load the entire lifetime of deductions in a lump sum payment, on the condition you would work there til regular retirement age?

For the sake of this example, let’s ignore inflation and keep it at a flat $1,000 per month. From the age of say 22-65. That equals 516x$1,000 payments. Now, if you had the option, would you take $516,000 upfront and invest it, or would you want to take $1,000 a month for ‘life’? This is akin to the lottery winner decision equation here, with the diffence being in that decision you’d be offered considerably less than $516,000 due to the present value calculations. I understand that this seems like a fantastical scenario, but in reality it is exactly what you are doing when you opt to not lump sum invest.

Doomsday Planning

But what if… aliens attack the earth with laser beams strapped to rabid rodents… (or insert your worst fear here) and the market crashes? Well, there is still something of an argument for taking less than $516,000 on Day 1 vs $1,000 a month for your working life. In fact, the greater the lump sum and the longer the time horizon the less effective lump sum investing really is. Even with a very small amount, comparing just a year of this ($12,000 vs 12x $1,000) LSI wins two times out of three over the past 64 years.

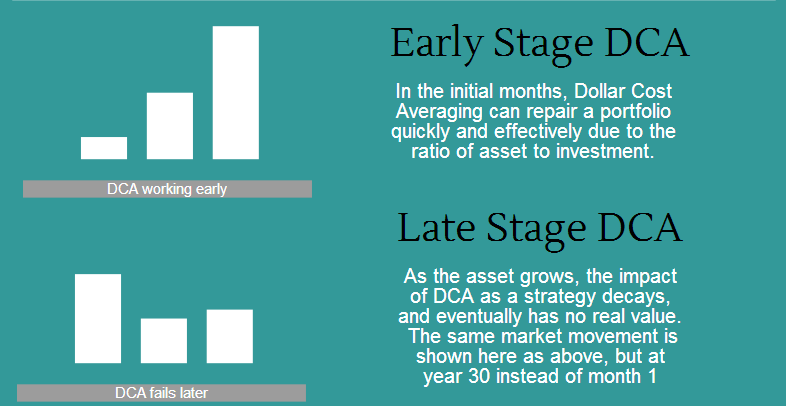

It’s all about the back end

Dollar cost averaging works best when the impact of the addition is high in ratio to the asset. This is the Repair Ratio. For example, if you were to see the future and know that the market is due to crash by 50% you might opt to DCA. If after investing $1,000 the market dropped, pushing the investment down to $500, month two would bring it back up to $1500, meaning that you would only need to see a 33.33% recovery to be at par. Or in the below example should month two have stagnant growth, but month three we see a 20% rally:

Month 1

- Starting Value $0

- DCA $1,000 [Market Drops 50%]

- Ending Value $500

Month 2

- Starting Value $500

- DCA $1,000 [Market Unchanged]

- Ending Value $1500

Month 3

- Starting Value $1500

- DCA $1,000 [Market Increases 20%]

- Ending Value $3.000 (par)

Compare with Lump Sum Investing, you would need to wait for 100% gain to return to your $516,000… scary thought right?

However, that’s the front end, if you instead look towards the back end and take another 3 months, perhaps say 30 years into the investment, with perhaps a 6% growth rate over that time:

Month 360

- Starting Value $1,004,515

- DCA $1,000 [Market Drops 50%]

- Ending Value $502,758

Month 361

- Starting Value $502,758

- DCA $1,000 [Market Unchanged]

- Ending Value $503,758

Month 362

- Starting Value $502,758

- DCA $1,000 [Market Increases 20%]

- Ending Value $604,509

This goes to show that the declining value of the DCA sum in ratio to the asset it is feeding eliminates its effectiveness over time. At the outset, your DCA makes a huge impact to a declining investment, but by the same token, it loses a huge amount should the investment increased in value. The decaying impact of DCA means that at a certain point you are as at the mercy of the market as you would have been if you had instead opted to lump sum from day one. Incidentally, just using an average again of 6% that lump sum would have grown to $3.1M, though of course the returns would have variance.

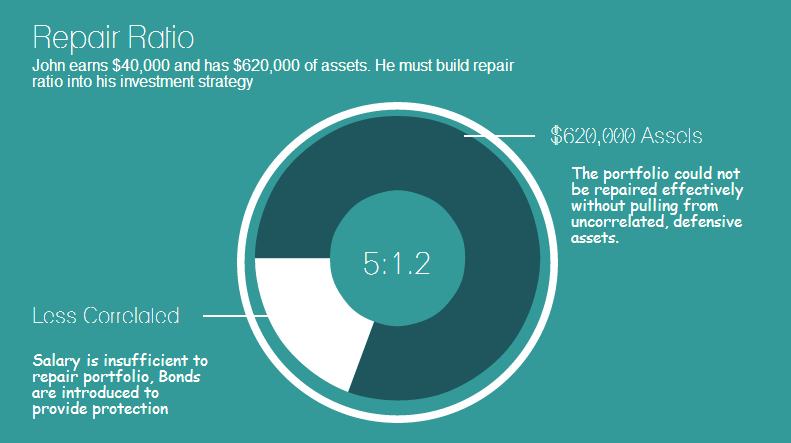

Repair Ratio in relation to asset size and correlation

As you can see from the above, if your DCA amount is de minimis in relation to your asset, it has no function. At this point, in order to protect your wealth you need to bake in repair ratio to your asset mix. This is the concept of studying portfolio risk and correlation. Remember that cash too is an asset class, and while cash offers repair ratio, it does not offer growth in a low interest rate environment. The root of the failure of DCA is that the cash sits idle, and while you are protected on the front end of the time horizon, you are losing out over time.

When we look at asset allocation, frequent mixes are Stocks/Bonds. While there is some uncertainty towards the Bond Market in a low interest rate environment, it remains a valid option to offset stock market exposure, however when relying on a volatile asset like bonds their repair ratio must be reduced by risk of interest rate rising and credit defaults. If you were to seek to protect a stock market asset with a bond market asset you must first calculate the repair ratio desired from the defensive asset, and then increase the amount required by its inherent risk value.

Repair ratio values are unique to everyone and are derived from risk tolerance

Example 1: John earns $40,000, and has $500,000 in stock market assets. He decides that he would like to keep $100,000 in uncorrelated assets to protect it from a downward swing. He opts for Bonds, which offer a greater return than a checking account, but the Bonds carry their own risks of devaluation through default and rising interest rates. As such, he should seek to hold a higher amount in Bonds, and targets $120,000 in the knowledge that they too could decline in value at the time that he needs to liquidate them in order to tactically repair his stock market investments.

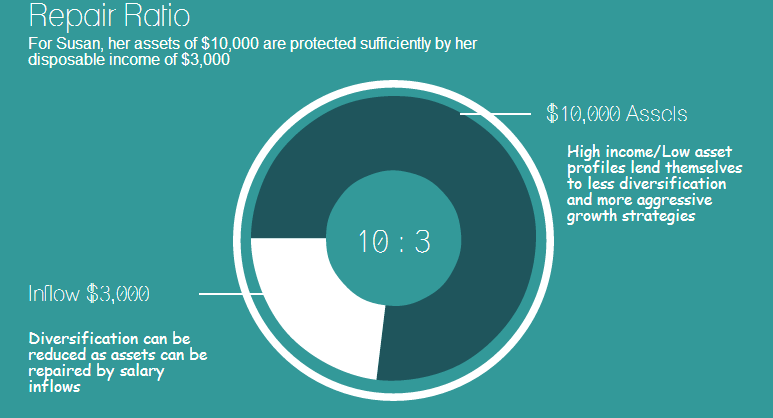

Example 2 Susan has just secured a job after Grad school and has $10,000 in stock market assets and a new monthly disposable income of $3,000. She does not need diversification into bonds to provide repair ratio, as her inflows are more than sufficient to repair a stock market loss.

In neither example would John or Susan need to DCA these sums. John would lump sum invest into an asset mix that held inherent defensive qualities, and Susan could consider being 100% exposed to a single asset class as the ratio to her inflows to her savings is high enough to protect it from loss. Of course, should something change in that equation, such as job loss then the mix would need to change, and this is where an emergency fund helps protect catastrophic events.

Conclusion

Nobody can see the future, and all investment decisions are guesses (hopefully with a degree of education) however you should be aware that the down side of DCA appears to outweigh the upside of it. What really matters is building an investment portfolio that is able to weather the storms of the market. For those at the start of their financial journey it may make more sense to be more exposed to a higher risk and reward strategy while their salary can provide repair protection. Once the wealth accumulated becomes too much for the salary to protect, or should a windfall payment change this dynamic, a defensive and diversified allocation is required to take over the job of repair ratio. Of course, in an ever interconnected world, finding uncorrelated assets is not an easy task.

I used to trade with a wealthy gentleman (and I use the term loosely) who would dollar-cost-average on an asymptotic basis until his average price was so low that when the company filed bankruptcy, he would exclaim, “See, I only lost 6 cents per share!”

Lol- that’s a great way to look at life!