The concept of a glidepath in personal finance is taken from an aircraft. As it reaches its destination the characteristics of its propulsion are adjusted to help it land safely, and smoothly.

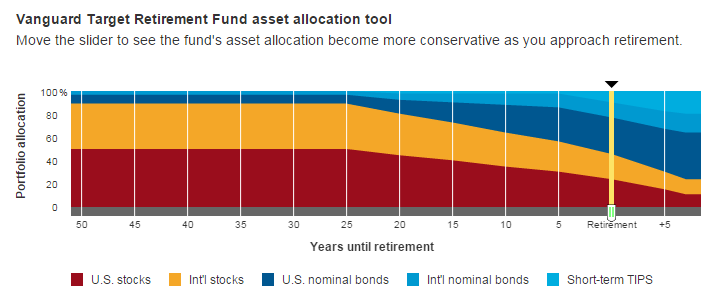

You will see this manifest itself in many ways, one might be in a Target Date Fund, here’s an image from Vanguard showing their approach to this, note how the chart starts out (age is on the X, bottom axis) with lots of red and yellow (both are stocks) and how the various blue colors fill in the gaps as time progresses? This is an asset allocation that starts out 90/10 (stocks to bonds) and ends up at retirement 51/49. It ‘glides’ there.

The reason why it is considered wiser to glide than switch is a forward looking risk analysis. If you get to age 65 (retirement) and decide you are going to finally swap from 90/10 to 51/49 you might find your plans going awry if the market drops in that year. With a glide plan the annual bumps are smoothed out somewhat.

How many glidepaths should you have, and what does it mean to have more than 1?

I mentioned recently about the concept of obligations being more important than debts. This ties into the multiple glidepaths notion. Let’s look at an example:

Lisa and Bob having been dating, they plan to get married, and have a child. From a cash flow perspective they have the following obligation (if elected) events:

- September 15, wedding, cost $25K

- October 15, baby is due, cost $0 thanks to the ACA

- December 16, buy a house. $20K downpayment

- 18 years from now pay for 4 years of college

- 40 years from now retire at age 65

Here we have a series of cash flow events which require payment due in a variety of ways. However, upon closer examination, some are hard targets, and some are soft.

Dec 16 is a hard target, if the bank doesn’t get $20K then Lisa and Bob don’t get their house. As such, it is important to eliminate risk from that $20K glidepath, pulling it down to an all cash position with enough forward looking risk analysis to repair it by Dec 16. If they are 90/10 into equities and on Dec 15 the market drops by 50%, what happens to that hard goal?

It could be that the market bounces back, which we do hope for, but from a planning perspective we are now gambling. However, if they have sufficient cash flows incoming to repair that remaining $10K, they would be able to still meet the hard target. They cash out the stocks, put it into savings, and save like crazy. Of course they are upset by this, but they suck it up and get it done. Depending on risk tolerance, this may be an acceptable risk providing that they are ok with the downside along with the upside.

Going from savings to investments

What we’re looking at here is basically the notion of savings accounts. But rather than having a ‘Home Buying Savings Account’ held at the local credit union, we are wondering if glidepaths are more effective. Furthermore, are there ways to diversify them without relying on cash? A classic approach to Bob and Lisa would be:

- Target Date for retirement account $10K

- 529 plan invested with target date for 18yrs $1K

- Cash like position for wedding $25K

- Cash like position for house $20K

- Cash Emergency fund $6K

What this creates, from the list above is a lot of cash… the question is do you need all that cash, because holding it comes at a price? The glidepaths for wedding, house, and emergency fund have already ‘landed’ are now risk free, meaning they are likely return free also. Yes, you need cash to pay the wedding, yes, you need cash to pay the house, yes you need cash to pay for an emergency. But don’t you also need cash in retirement? Why is it safe to be in equities there? Investment time horizon is the key.

The what ifs?

What would happen if they were 100% invested in equities and the market dropped 50%? It’s likely that their wealth would drop in proportion. That would mean:

- Target Date for retirement account $10K becomes $5K

- 529 plan invested with target date for 18yrs $1K becomes $500

- Wedding fund $25K becomes $12.5K

- House fund $20K becomes $10K

- Emergency fund $6K becomes $3K

Devastating… perhaps…

They’d still have enough money to pay for the wedding though, by using the money from the House fund and Emergency fund, or they could cut some costs on that too. But they’d have no money saved for the house. Strangely, most people wouldn’t care about the retirement account as much, because ‘it has time’ to get back.

From the above, you might think that the risk profile is too high, because the impact of the loss is too great. But what happens if you then discovered that they both have just secured jobs that pay $250K per year, and that the house fund can be replaced in a month? The risk is may seem acceptable again.

What if the salary is lower, perhaps they have enough money left over to save up $5000 per year, and they have a year until the house deposit is due? This creates a situation where considered in isolation, the house fund could decline in value by 25% (20K to 15K). If we were in equities 50/50 with cash, and the market still dropped 50%, that fund in isolation would be OK. However, when we consider multiple savings goals, the following would occur:

- Wedding fund becomes $18750

- House fund becomes $15000

- Emergency fund becomes $4500

They’d then have to borrow $6250 from the house fund to top up the wedding, leaving a balance of $8750, with a year to save $5000, and a shortfall of the $6250 when it is time to buy a home. Too much risk?

Let’s not forget that they have $4500 in an emergency fund, a 529 plan which is tax free due to its decline in value, and future contributions to that which could be reallocated. They could still buy that house.

Perhaps a smarter decision here would be to dial down the risk further. What about the following:

- Wedding 20/80 (stocks/cash)

- House (30/70)

- Emergency Fund (40/60)

All we are doing here is making the glidepaths more aggressive, and rather than landing in cash, keeping a little invested. In this example, a 50% decline followed by a 12 month flat market creates the following:

- Wedding fund $22,500

- House fund $17,000

- Emergency Fund $4,800

They’d borrow $2250 to repair the wedding fund from the house fund, leaving a shortfall of $5500. This would be replaced by $5000 in savings over the year, and mean that they would only be $500 short of buying the house even with zero asset appreciation. This $500 is actually replaced via tax loss harvesting. The total combined equity allocation across all funds being

- 20% of $25K = $5K

- 30% of $20K = $6K

- 40% of $6K = $2.4K

- Total invested: $13.4K

- 50% decline = loss capture of $6.2K

- $3K applied against regular income rate of 25%= $750, which covers the $500 deficit if assigned within the budget.

The big picture

Here we are layering multiple glidepaths, and show how the time horizon can allow more aggression because we can replace greater losses with other income, the “house fund” can be 30% equities as you have 1 year to get the funds saved up again. Ultimately you may wish to say ‘I’d rather be sure that I have the money’ because there’s no saying that the market can’t drop every year, so even the final example above can fail.

The decisions made at times like this should be a combination of risk impact and risk likelihood. The final example gives a scenario where it will always be possible to pay for the wedding, even a 100% drop in equities would allow enough to be borrowed to make things work. But it also brings a risk that the house may need to be delayed. Furthermore, the problem with the lack of house fund could be kicked down the road by tapping other accounts correctly, but if you keep on kicking problems down the road, at some point you need to face them. Finding the balance in optimizing such things is a personal issue, but most financially sophisticated people should be able to take on more risk than is thought, which should help with achieving long term goals.

Leave a Reply