I just read a post from Dave Ramsey, well known Personal Finance expert and was surprised at the lack of thought in the theory displayed. I think one of the biggest problems we face in taking charge of our Personal Finances is being able to see through the soundbites and marketing gimmicks and get to the truth of the matter for savings. I actually picked up on this article from another finance blogger who was citing it as gospel. Another case of the blind leading the blind…

These days the line has blurred between bloggers and traditional news sources when it comes to sources of information (and misinformation) and quality control is hard to come by. It is clear that both in the blogosphere, and the traditional press, there are different levels of quality – and sometimes the simple (and wrong) answers sell. Well, lets dig into Mr Ramsey’s post to see if it is better to have a cool soundbite for a dinner party that shows your knowledge of a concept, or if it is better to take that extra moment to dig behind the story to see if its actually true or just fantastical.

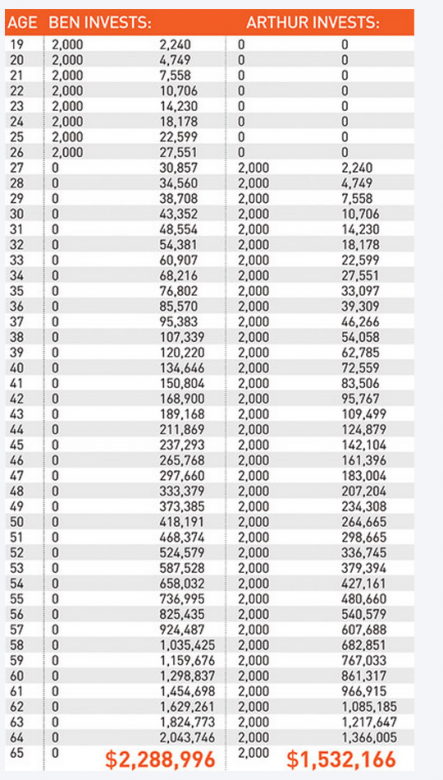

The premise behind the theory is that if you contribute $2,000 per year between the ages of 19 and 27, a total of $16,000 to a mutual fund, you will, due to the magic of compound interest have more money when you retire than if you start saving at the age of 27 and contribute $2000 every year until you are 65. They call the kids in the example Ben and Arthur respectively. Sounds like a great story to tell at a party right? Here is the post in full How Teens Can Become Millionaires

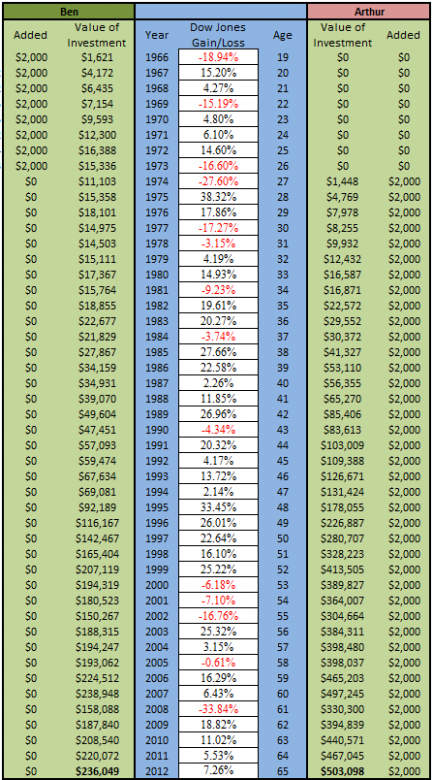

Here’s the ‘data’

Here’s the ‘logic’

And this is why it is complete rubbish:

Compound Interest can provide gains just as described above, there is no doubt about it. However, they are seeking a return that is ‘averaged’ the average 12% return (which I might add is unrealistically high) means that the number is ‘averaged’ out over good years and bad years. And if you are following a strategy that does not add money to the investment during the bad years – also known as Dollar Cost Averaging, you cannot possibly achieve the goals being discussed here.

Compound Interest Fails when Interest Rates are Averaged

It is critical to understand that an average rate is variable, and this is a huge deal for any Investment. If you invest a Fixed Amount into a Variable Rate Compound Interest Fails. Compound interest only works if the Rate of Interest is consistent throughout, if it is variable, IE the price raises and falls due to the market then it will fail unless you can counter the rate movement with injecting more external money – you have to buy more when your Investment is losing money to survive.

Standard Deviation is the key

Whenever there is talk of averaged rates there is a very important mathematical term known as Standard Deviation. I remember falling asleep in many Economics and Statistics classes when the subject arose, but I blame the miserably boring Professors for that, rather than the subject matter. Standard Deviation means how wild the fluctuations are from the norm, when an average interest is 5% and the standard deviation is 1% then the most your rate would be is 6% and the least 4% – 1% either side of the average. However, when Standard Deviation is say.. 10 and the rate is 5% that means that some years you could earn 15% and some years you could lose 5%… that’s pretty epic. For what it is worth, the standard deviation on a stock within the S&P 500, is about 15%, it has been even higher than that too in very volatile years.

The Impact of Inflation

In an overly simplified world, you could achieve the growth of $16,000 into over $2,000,000 if the amount was fixed, IE if it was a steady and guaranteed 12% such as you could get with a Certificate of Deposit (CD) but even in that scenario there would be variable rates that impact the real return – inflation would fluctuate year to year, and in doing so your real rate of return would differ substantially.

Inflation reduces the value of your dollar/pound/peso, so for every Percentage Point you seek in growth and appreciation you have to first balance out the inflation number then find your ‘Real Rate of Interest’ The Federal Government aims to keep inflation at around 2%, however there have been instances in the past 40 years where it has been as high as 13.3% if you are earning 12% and inflation is 13.3% then you are actually losing money every year. Incidentally, that year was 1979 and if you were invested in the Dow Jones Index you would have seen growth of about 5.5% or with inflation a ‘real loss’ of about 8% that year….

Actual Performance of Money Left Sitting

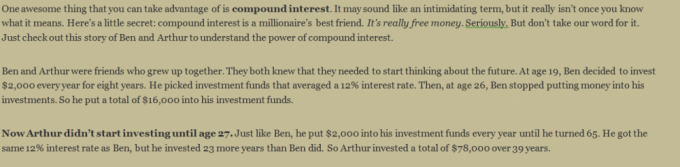

Dave’s Ben and Arthur story highlights the power of investing early and then ceasing additional funds being put into the investment. This is where it breaks down as a strategy. By doing this you are not buying on the ‘dips’ and that means you are like a boat bobbing along on the waves, when it goes low you ride it out, and when it goes high again, you don’t gain anything other than getting back to where you were before. Let’s look at the performance of $10.000 in Vanguards VTI Fund – this is a broad market index fund, investing in over 3,000 shares that make up the US Stock market.

These examples are from Vanguard’s website and show how $10,000 would grow if left over time within an ‘average’ rate of interest, it is a much more realistic one too as it is taken from actual performance. What you will see is that the sharp fluctuations in earnings that are due to the market movement. It is this market movement that prevents 12% Compound Interest to be true. In fact, when picking an investment vehicle like a Mutual Fund you should know that you could actually lose money every year, or invest your $2,000 every year for 8 years and end up with no gains at all.

Dollar Cost Averaging to Mitigate the Variable Rate of Interest

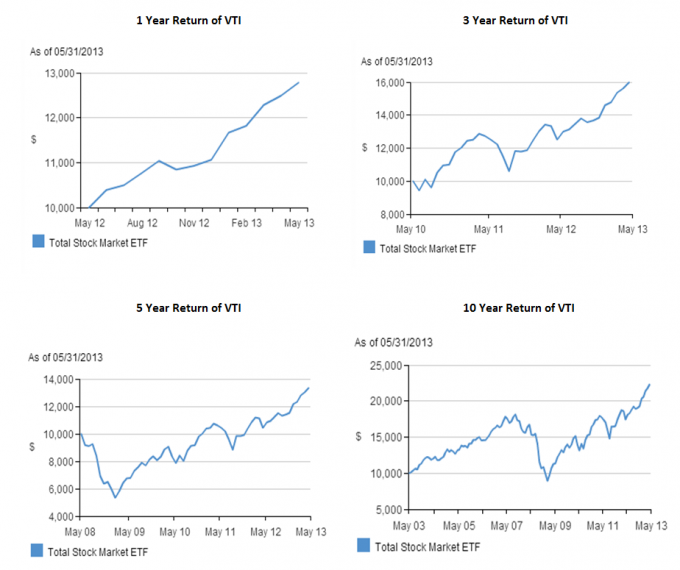

As you can see from above, the entire strategy fell apart in 2009, ‘Ben’ had seen growth of his $10,000 up to $18,151 in the years up until the high in 2008, but that year the value dropped by 50% and his investments were worth $9,700 – this is what happens with the stock market folks. Let’s look at what that did to Ben with his $2,000 per year for 8 years, then nothing more added, I’ll use the Dow Jones, as the guiding factor here, and start it from Year 1 so we see realistic numbers, please note that these are not taking into account inflation:

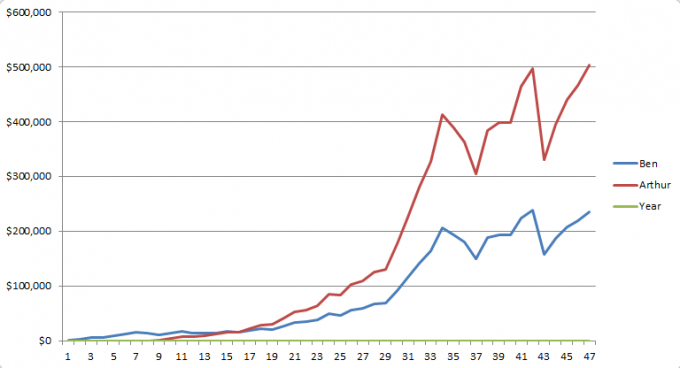

After such a short period of time (from an investment perspective) we can see that Ben is actually still doing better than Arthur with these real numbers – this is because the impact of starting savings 8 years earlier is still very relevant when considering a time frame of just 18 years. Incidentally that actual ‘average rate of return on the Down during this 18 year period was 8.49% though you should consider that number is not what you would earn in any fund as they take a cut of the pie as a management fee. However, when we look forward a little into the future we see where the problem lies with not adding more.

Unfortunately, despite my best efforts I cannot predict the future, and as we know past performance does not guarantee future results, but to be frank I cannot think of a better measure for looking at two investments like Ben and Arthur’s here than going back in time, and using the actual results of the Dow, this is when things get interesting.

If we look at the chart for this data we can see that the tipping point occurs after 18 years and is much more apparent at 29 years in, once achieved Arthur’s dollar cost averaging leaps ahead of Ben’s. And whilst they both get burned very badly in the horrible year of 2008 should they both retire this year at 65 using the strategies laid out by Mr Ramsey it is Arthur, not Ben that is winning- with over Double the amount of money saved… and sadly, neither of them are Millionaires.

I like the idea of encouraging the young to invest at an early age, and certainly the sooner you start the better, but one of the biggest problems with society today is that they are being misled by people who they think they should trust, and if they don’t take a closer look at things today they will reach retirement age with a vastly different number in the bank than they were led to believe.

We cannot put all the blame on others though – it is up to us, the individual to scrutinize the data, and learn the truth. If we rely on others, supposed experts in their field we can end up in all sorts of trouble, when they over simplify for the sake of a soundbite. The grain of truth in the story of Ben and Arthur is the common sense idea that saving sooner is better, but lets not lose all sight of reality when trying to explain a simple idea like this…

Dave’s Ben and Arthur chart is used ONLY to teach the impact of COMPOUND INTEREST. It is not his retirement plan to only save for a few years and then quit. Dave teaches to get debt free as soon as possible and then invest 15% of your income for the rest of your working life. If you invest 15% of your income from age 30 until retirement, you are taking advantage of the wonderful world of Dollar Cost Averaging.

Dave has good sentiments but some of his examples are inaccurate to the point where they can confuse and mislead people.

This is an unintentional side effect and I think his general approach and motivations are positive.

Matt, thanks for doing this analysis. I was just explaining compound interest to my 6 year old son using the Dave Ramsey example you cite above. I was crestfallen to find your results since it meant I would have to go back and tell my son that the principle was essentially inaccurate.

Since I’m a bit of a money nerd, I wanted to test some variations just to make sure I was giving him the most accurate information I could. What I found was kind of interesting and I thought I would share it with you.

*As you pointed out in your example using the DOW and starting in 1995, Ben was still ahead of Arthur. The DJIA returns for 2013 (26.5%) make this even more the case and confirms what you say about short run returns being better if you start earlier.

*I was curious to see where I would be today if I had been Ben. I was in 19 in 1992. Had I went with the Ben approach, today I would have a balance of $57,309. Had I went with the Arthur approach I would have a balance of $42,793. This seems like a pretty good mid-term comparison as it is near the half-way point of the plan.

*Indeed in 2008, I would have lost nearly the equivalent of my entire initial Ben investment (-$15,495) but would still have a balance of $30,349. Comparatively, as an Arthur investor I would have lost less than half of my initial investment to that point ($18,000 invested / -$7,497 in 2008 losses). And by Dollar Cost Averaging, an Arthur investor would be back above the 2007 highs in less than 2 years compared to a Ben investor taking 4 years to recover. Still, at no time during the crisis and recovery did Arthur have a larger balance than Ben.

*Looking at the longer term, I wanted to see at what point did Arthur’s investment strategy actually surpass Ben’s. I discovered that Ben’s investments outperformed Arthur if he started in any year going back to 1974. That is, if you turned 19 in 1974 or any year since then and acted as a Ben investor, you came out ahead of Arthur up through 2013. Granted, starting in 1974 gave you only a few hundred dollar lead. Yet starting in 1975 gave you a remarkable +$40,000 lead. Nevertheless, you are correct with your data showing a start in 1966 did not work out for a Ben investor.

*In fact, the DJIA didn’t work out for a Ben investor from 1901-1973. But from 1974-Present, Ben is ahead.

*So I wanted to compare to the S&P 500 to see how the broader market performed. It turns out that the S&P works out for Ben much more often than the DJIA. In fact, from 1926 there are only two periods where Arthur outperforms Ben to age 65 or to 2013 if younger. From 1926-1930 and from 1959-1967. If you were not unfortunate enough to be Ben turning 19 during any of those 14 of the last 87 years, you have outperformed Arthur if you invested in the S&P 500.

Caveats of course that during a lot of these periods you couldn’t easily buy the Dow or the S&P as Index Funds and ETFs weren’t always available. But we can easily do those things now. And of course these numbers (both yours and mine) treat the investments as lump sums on Jan 1 of each year. And of course, the effects of inflation play their part. Interestingly, once you include 2013, the average return of the S&P 500 is in fact 12.03% (though the CAGR is 9.85%). On the other hand, none of these returns account for reinvested dividends which would make your returns quite a bit better.

At the end of the day, it would appear that the Dave Ramsey advice and example turn out to be fairly accurate unless you really had some bad luck with your date of birth. All that said, I agree with the other commenter that you will get a lot further by investing 15% of your income and Dollar cost averaging in.

Again, thanks for your analysis and spurring me on to some of my own. I’ve included the sources below that I used to get historical returns.

Sources:

S&P returns since 1926: http://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/S%26P_500_index

DJIA returns since 1901: http://www.forecast-chart.com/historical-dow-industrial.html

DJIA returns 2013: http://www.cnbc.com/id/101303244

I think it is great that you are sitting down with a 6 year old to explain compound interest. As for your analysis, let me suggest this:

In order for either Dave or myself to be correct relies upon market timing. Therefore it is a flawed example. Furthermore, as Jennifer stated it is not supposed to be a recommendation that you invest only for these first few years then not at all.

As such, my recommendation would be to not use Ben and Arthur to explain compound interest, find a different example that factors in the other important subject of Standard Deviation OR keep it simple, and only talk about compounding in a fixed interest environment. I think if you cannot explain compounding within the volatility of the market it is better use of the lesson to simplify the interest, and caveat the lesson briefly with the fact that it only works consistently if the variables can be controlled.

It is my personal opinion that short term volatility will increase as boundaries to entering the market lower, and tools to trade, along with asset classes become more varied, as such, looking backwards too much for data will become increasingly unreliable.

Therefore the best lessons we can teach is to rip up Ben and Arthur and instead find a parable that discusses Compounding, Standard Deviation as mathematical concepts and how volatility affects the markets.

Your analysis is absolutely correct. But I have to echo what Jennifer wrote. Dave is using the Ben and Arthur illustration to explain compound interest and nothing more. It’s not a retirement investment strategy and he makes that quite clear in his teachings. By pulling out this one example you are misrepresenting his whole strategy for getting out of debt and saving consistently for retirement. He uses Ben and Arthur to jolt the people that need it most and then he lays out an excellent strategy for being able to retire with dignity and not having to depend on social insecurity.

Gary,

The problem is this. I wrote this post after reading about someones total misunderstanding of this from a personal finance site, they did not realize what you and Jennifer do, that the story is flawed, but has value in helping people take the right steps forward.

What we need is examples that achieve his vision better, by being accurate in their logic AND helping people in the way he seeks to. I think he does a lot of good, but my biggest concern is that when you are rebuilding trust in financial education it is critically important to be correct in your examples.

I can still see value in ‘being wrong’ yet doing right, but I would prefer both to align.

Your analysis is accurate and very detailed if I may add, but I think it is a little off base. Dave suggests that we invest in growth stock mutual funds…which in fact, have earned a 12-13% compound return over time. This accounts for years such as 2008 when everything went to hell. Your example follows investing your money in the DJIA or similar index such that earned a 7-8% compounding rate over the past half century or so. There are many good companies and mutual funds that consistently beat this rate (to include down years). I think Dave’s example is more accurate than you think. You are correct that no fund will earn an exact 12% every year, but I personally invest in growth stock mutual funds that beat 12% long term.

Also, thank you for writing this post because it made me do a ton of my own research to further my understanding on this matter.

Net/net-Get the money in the market while you are young and let compound interest work to your advantage. Don’t stop investing (of course!!) so continue to dollar cost average. If you are brave enough invest even more after -15% downturns.

I think everyone missed the point. If people understood the point BEHIND the Ben and Arty illustration, we would have a lot more millionaires. The point is that saving early and often leads to big payoffs. The point is also that you don’t need 99% of the math you just spent wasted hours on describing. Can you grasp the concept that saving early is better than saving later? Can you grasp the concept that saving = $$$? It’s as simple as that, friend.

Absolutely it’s about saving, which is a different thing from compound interest.

You should be a news reporter. Your ability to take things out of context and then spin them to fit the title of your article is second to none.

Matt,

Thank you for this. While I have read a couple of Dave Ramsey’s books and am working to pay off all my debt, I had actually been teaching my son’s that the Ben vs. Arthur was “truth”. While I do realize that Dave’s teachings are for life long investing, it really should be noted that this outcome is highly unlikely. Yes it is a “shocking example” of how compound interest COULD work, but it is unrealistic.

Also, if I remember correctly, he does say it is relatively easy to get a 10% return in his books/podcosts, which is not so easy to get and requires quite a bit of risk. My daughter’s college fund made 22% in 2017, but for 2018 it only grew because of the money I added each month during the year, and even that barely covered the losses.

Thanks agian.