Whenever you close a position in a taxable account, a tax recognition event occurs in that year. When it comes to reporting this to the IRS,the process isn’t as smooth as it should be, errors occur at various stages of reporting, and whether you use a tax preparers such as CPA’s or EAs (Enrolled Agents) or a DIY program, errors are likely to occur if you don’t ask the right questions. Garbage In, Garbage Out is the phrase to remember here.

Before we examine the major problems that will be encountered, let’s first understand the reporting process. Due to the complex tax process we have, Taxable Gains (and Losses) are calculated on the Schedule D of form 1040. The Schedule D is a 2 page, three part form.

- Part 1 Short Term Gains and Losses

- Part 2 Long Term Gains and Losses

- Part 3 Calculations

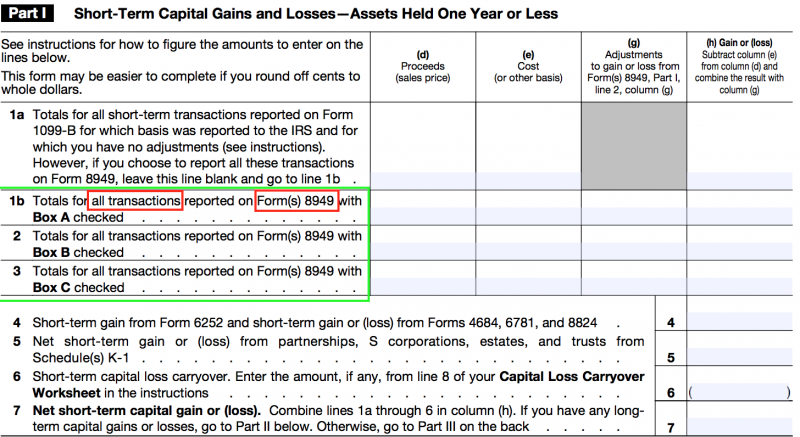

The problems I typically find occur within Part 1 and Part 2. This is the Garbage In, Garbage Out. Let’s look at Part 1 for an example:

Schedule D Part 1

As you can see, the form has 3 parts [highlighted in green] and it refers to all transactions on Form 8949, this is a key point where problems arise.

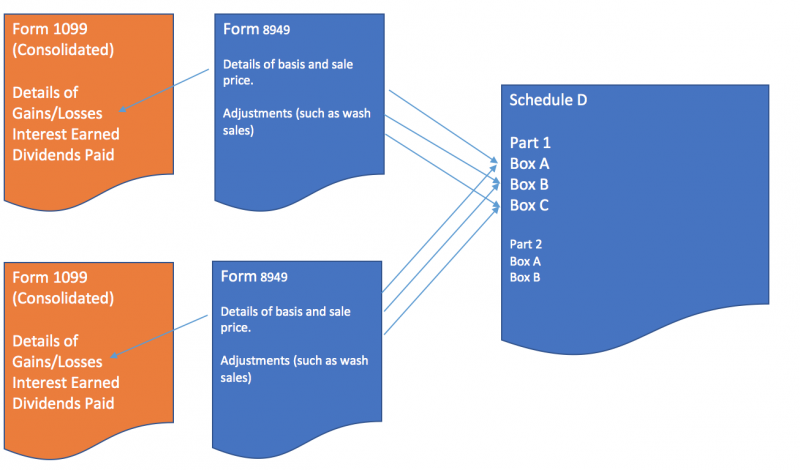

The broker will provide a ‘worksheet form for form 8949’. This is a tabulated set of data that is to be transferred into the Form 8949, it is essentially the same as form 8949 other than the format. The totals from this form may, or may not be transferred into form 1099-B. If your tax software or professional asks for form 1099-B, or consolidated form 1099 to create the Schedule D, you would well be reporting erroneously.

Golden Rule #1

Do not allow your Schedule D to be created from 1099s alone. Doing so will mean that you may be perpetuating errors at the 8949>1099 phase. Let’s look at the process of reporting from a high level to see where this error point occurs:

Worksheet form 8949 is the key to the 1099-B and 1099-B section of the consolidated 1099. If you read the 8949 you can see problems, which tend to come in the form of no reported basis. Sometimes you might see a sale reported for the year, but no basis for that sale for a number of reasons. If this is not identified it might be that the entire section of the form is not transferred through to the 1099 (and the Schedule D if your Schedule D is based on 1099s rather than 8949s) and you can fail to report that transaction.

Problems with the basis

There are several things that might have occurred to create problems with the basis that is being shown on the 8949, the first thing I would advise people to do is confirm that the investment isn’t subject to special treatment of basis. This most commonly can be seen with Energy related funds, such as MLPs or Canadian Energy Trusts. These investments have special tax treatment which can seriously complicate gain/loss reporting. Many people initially invested in these due to their attractive dividend yields, however the dividend is often taxed (in part) as a return of basis.

MLP and Canadian Energy Trust Taxation using this return of capital model is sold as an attractive option to defer taxes on gains, but can complicate scenarios where an investor believes that they have a capital loss. For example, if a fund was purchased for $100 and paid $10 per year in distributions it might be that $9 was a return of capital (ROC) and $1 a dividend. The ROC would reduce the basis in the fund to $91. Eventually, the basis would reduce to zero.

Let’s imagine that the fund dropped from $100 per unit to $25 over the course of 15 years. An investor who bought $10,000 of the fund may believe that they have a capital loss of $7500 to report, however, because they have a basis of zero, it would actually be a gain of $2500. A clue as to whether you are invested in such a fund is if you receive a K-1 rather than a 1099 for your dividends.

If you have a ‘normal’ fund or stock, and you just have bad recordkeeping you might need to look up historical prices. Yahoo finance, along with other services, can be used to look these up. If you can say with certainty that you bought the stock/fund on day X you can then look up the price on that day and use that for the cost basis. Here’s the Yahoo Tool.

Can you ‘guess’ the basis?

If you really cannot prove the basis, the IRS will assume it to be zero. However, if you could make a reasonable case for it, you might want to consider reporting something other than zero. This would create a situation where you’d have to justify that in an audit though…. For example, if you were certain that in a year you bought a position, but due to bad record keeping you weren’t certain of the exact day that you entered the position. The IRS will not allow you to use an ‘average’ price for stocks, but mutual funds have an exception to that:

You can use the average basis method to determine the basis of shares of stock if the shares are identical to each other, you acquired them at different times and different prices and left them in an account with a custodian or agent, and either:

- They are shares in a mutual fund (or other regulated investment company);

- They are shares you hold in connection with a dividend reinvestment plan (DRP), and all the shares you hold in connection with the DRP are treated as covered securities (defined later); or

- You acquired them after 2011 in connection with a DRP.

Source, Pub 550 Special Rules for Mutual Funds

However, it might be a valid argument for you to look up the historical stock price for the month or year in question, select the lowest possible price, and use that as basis. The decision on whether that should be done or not should come down to a cost benefit analysis of the tax saving, and by consulting with a tax professional. This strategy might work providing you had proof that the stock was actually purchased, rather than gifted or received in some other manner. It is important to remember that in some cases, even a reporting of zero basis may have zero taxable impact due to tax brackets.

So, when it comes to tax time, remember to keep an eye on your 8949s, they are often overlooked by individuals, and by tax professionals as people rely too much on the trust that 1099s are accurate. If you do see things that are unusual, first consider if the security itself has some special treatment, and then start diving deeper.

Timely. I’m struggling today with basis for a mutual fund bought in 2011 and cannot find my original paperwork and it’s one advisor and one custodian ago. Yahoo it is!

Am I misunderstanding something? You say, “However, it might be a valid argument for you to look up the historical stock price for the month or year in question, select the lowest possible price, and use that as basis.” Shouldn’t it be the highest possible price? Don’t you want a high basis so you have less of a gain or did I read too fast?

If bought Ford in 2007 but can’t remember the exact day.. It’s not exactly fair on the poor IRS to propose the highest basis day.

Whereas the lowest basis day is both plausible and perhaps acceptable.

I resolve this entire problem by not using Schedule D at all for the hundreds of trades I do.

Want to guess how?

You can just add various into Schedule D anyways… But tell me more!

List “Securities Trader” as your profession. Make a 475(f) election . All gains and losses are are marked to market at year end whether closed or not.

Schedule D is ignored and Form 4797 is used ‘Gains and Losses on Sales of Business Property”

In addition you can

a) deduct expenses on Schedule C (it will always be a negative Schedule C but ins’t considered a hobby

b) FICA is not paid on gains in securities trades even if it’s a buisness

Interesting. Completely impossible to do as a regular Joe, but neat for you Traders 🙂