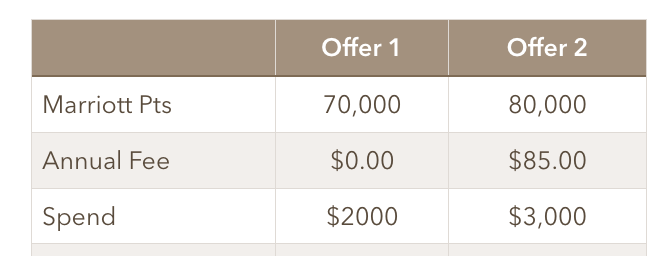

I wrote yesterday claiming that a 70K no fee might be better than an 80K, the people being paid to promote the 80K offer disagreed with me, as did Ben, who made a fair point. I’d like to help explain the math as simply as I can when it comes to valuations.

Points have variable values

If you need the points, they are worth more than if you don’t. That means we should all value points differently to one another, and we should also value them differently based upon our goals and needs.

This is critical. You shouldn’t say points are worth 1 cent each, so if you buy them for 0.85 cents its a smart move. My own rule of thumb is to pay no more than 1/10th to 2/10ths of a cent for speculative points. Though more often than not I would pay nothing, or pay less than nothing for them.

The 2% rule works, until it doesn’t

Everyone should have a 2% card. All spend has to be calculated against the opportunity cost on that 2% card. A simple example would be:

You have a 2% card (because you are everyone) and you receive an offer in the mail for a (let’s pretend) shiney new credit card, that offers 1 Wowzer Point per dollar spent, and a 25 Wowzer point signup bonus if you spend $10,000 in a month. Let’s pretend Wowzer points are ‘generally’ worth 1.5 cents each.

You simply run the math, you need to spend $10K somewhere to trigger the 25 pt bonus, for which you’d get 10025 Wowzer points. Deal, or no deal?

- 10025*1.5 = $150.38

- 10000*2%= $200.00

You can see that chasing a sign up bonus costs money, so the sign up bonus must be worth more than the lost money. This is a solid principle, it only really falters when you start hitting numbers that make the 2% company question your spend, and therefore you need to consider the value in diversification. At some point, you may need 1x cards, and if you can find ways to earn well enough, they still make a profit.

In the case of the above Wowzer card, you’d have to get a signup bonus of about $50 to make it smarter than the 2% card. At the same 1.5 cent value, we would have to have a bonus of about 3400 pts to kinda break even.

In the real world though, you need to add on a little juice for things like:

- The hard pull

- The time to apply (not major, but it is a bit of an effort)

- The breaking of loyalty to 2% card

- Some other things that I haven’t thought of right now

So let’s say we’re now at 10,000 Wowzer points bonus just to get a foot in the door, but wait, just as the door closes….

Enter the salesman

A knock on the door… hello good sir! I hear that you are in the market for Wowzer points and are willing to value them at 1.5 cents a piece.. well guess what I have for you today! The chance to apply for a new credit card that has TWELVE THOUSAND points for the annual fee of $20! That means that you are buying them just a penny a piece – and since you value them at 50% more than that – YOU HAVE A BARGAIN!

You might ask yourself why more often than not it is the person being paid to sell the snake oil that thinks it better, but I digress.

Let’s do the maths.

People struggle with this because they omit the 2% rule. Zero confuses them. Here’s why:

So they calculate as follows:

- 0/70000 =0

- 85/80000= 0.0010625

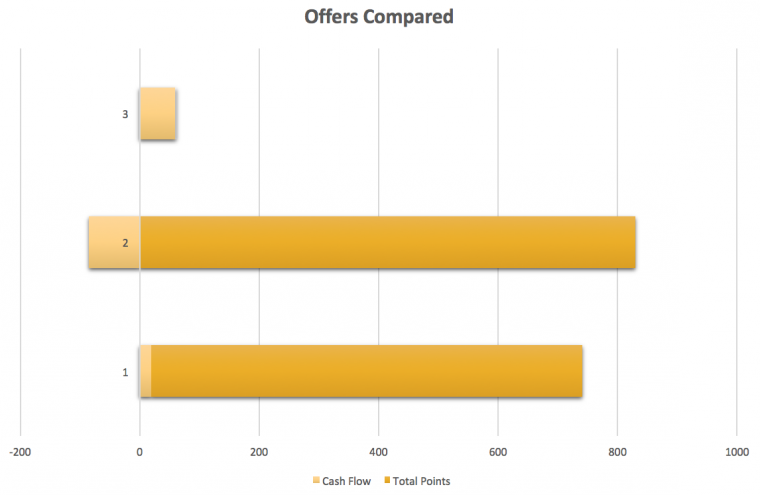

Seems cheap right? You can buy the points at 1/10th of a penny each (within my ‘ok zone’) but also, you can buy them for zero… which is very much plum center in my ‘great zone’. But the zero makes it weird for some, so I’d like to factor in the 2% rule to help us appreciate the pricing more. I’m also going to bring in a placebo.

Net Worth Impact

OK this is going to get a bit weird, but bear with me… I’m proposing that the 2% card increases our net worth by $60, whereas the fee free Marriott increases our net worth by $20 and ‘grants us some points’. And the Fee card, reduces our net worth.

Sure, there is 11,000 more points on one offer than the fee free one. And absolutely, these points have a value. But what’s the value, and how much is the snake oil man marking up? Let’s look at the placebo again for the answer.

Fee free $2,000 spend could have earned $40. Therefore we ‘bought’ 70,000 miles for $40. Our price is 0.00057142857. A number so small my brain cannot convert it into dollars for you. Let’s now multiply that back out by 11,000… $6.29. So we’re being sold something for $85 that we’re buying at $6.29… nice work guy!

Would I ever do this?

Yes. But not right now. That is why I said ‘perhaps‘ when I titled my earlier post PSA – the Marriott 80,000 offer perhaps isn’t worth it. There are times when I might pay more, even this much more to complete a transaction. For example, I guess I now have about 300,000 Marriott pts from this last round, if there was an award level at 310,000 I might be prepared to pay the markup for it.

The key is simple. A greater offer, that comes with a cash cost is not a superior offer unless you are at a place where earning the points in this manner makes immediate sense for a redemption. Getting 83K to push you 20K over your goal is silly, as is getting it speculatively. It must be a very narrow and targeted need. So don’t get wrapped up in the hype.

I completely agree with your approach but not the definition of implied “Offer 3.” The more intellectual bloggers (and I do mean that sincerely), use the opportunity cost 2% to calculate value very often. I think a more nuanced view is needed. If the minimum spend is met by displacing spend you would have put on the 2% card, then yes, the opportunity cost is 2%. However, if you are manufacturing new spend to hit the minimum spend, there is no opportunity cost. Yes, I could have pulled out my 2% card at CVS and swiped it. But I would never have gone to CVS to use a 2% card. The only reason I’m there is an incremental trip to satisfy a minimum spend requirement.

A second point, and the biggest reason I take issue with imputed values such as Freequent Flyer’s and Frequent Miler’s is that there are limitations on 2% card usage. Some are explicit (credit limit) and some are not (surprise shut down due to overuse). The explicit limitations are enough to call into question assuming a 2% (or 2.1% or 2.2%) opportunity cost for all non-2% card usage. If I max out 2% cards buying Amex GC, the line is used up for at least a week just waiting for them to post. Plus any time it takes to get payment in and posted. The 2% isn’t attainable during that time, so it’s not a realistic opportunity cost for calculating the cost of using other cards. Similarly, on the implicit limitations, I can’t put unlimited spend on a 2% card, even assuming instant purchase and payment processing. At some point the issuer is going to shut me down for suspicious behavior. Of course none of us know exactly where that point is, but it’s unreasonable to assume that all spend should have be put on a 2% card.

Yeah I agree, I mention 2% rule works ‘until it doesn’t’ and that is at scale. It’s still a good base line.

Problem is that everyone is different, not everyone does AGC etc, so finding a baseline for the benchmark isn’t really straightforward.

i like your analysis and thinking on this issue. great way to point out what many of us in the game overlook.