When I was 10, I had to give a class presentation on a foreign country of my choosing. I’m not exactly sure how I settled on Denmark, but I did. I guess I thought Denmark kind of looked like Michigan, and was also in Europe, which was by all fourth-grade standards much fancier than Michigan.

I’m a bit proud I knew what Michigan looked like when I was in the fourth grade.

I don’t remember much about the presentation itself, except that it was pasted on a black cardboard poster, which was considered quite edgy for the time. I also remember informing my fellow classmates that people from Denmark were Danish or the “Danes,” and that the Danes ate quite a bit of fish, enjoyed ships of all kinds, and participated in “socialism.”

This last bit elicited a strange sound halfway between a snort and gasp from my teacher, so I knew I was on to something.

During the obligatory question and answer period, a particularly annoying classmate – who later became a good friend – dared to ask what socialism was. I confidently answered it had to do with everyone being the same and contributing the same thing and that it was very different from the United States, which was certainly not socialist.

I also threw in something about “communism” and “taxation without representation,” the latter because I figured the Brits and Danes may very well have been in some sort of European cahoots.

I found such words generally well-received when expressed by a fourth grader, while also having the added benefit of allowing graceful exits from topics I knew nothing about. This was the year of Bush v. Gore, after all.

And so, my presentation was a great success. I got a ++ or A++ or whatever grading scheme was appropriate for 10 year olds back then. More importantly, I was proud of my newfound understanding of a Michigan-like country on the other side of the world.

Danes ate lots of fish, had a flag with a frustratingly off-center white cross (I had to re-draw this several times), sailed tall wooden merchant ships, and were socialist.

For a while, this was all I knew, and needed to know, about this far-off Scandinavian land.

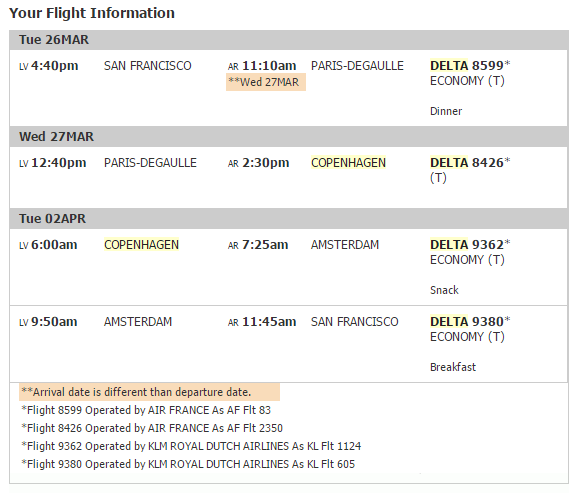

But a few years ago, I was suddenly caught by below-market fares to the Kastrup International Airport.

Not one to let a low-fare pass me by, I jumped at the opportunity.

I’ve wanted to write about Copenhagen for some time now. I just didn’t know how to frame it. Should I add to the endless 72 hours or weekend in Copenhagen articles? Would I adopt a Bordain-esque take on my layover in Denmark?

Besides the fact that my stay in Copenhagen lasted beyond these conveniently blogged about timeframes, I have to admit that my reasons for visiting Denmark were perhaps not as sporadic as the traveler in me would like you to believe.

You see, I’ve always been fascinated by design. I don’t have a great definition for what I mean by “design,” except that it has to do with how something looks and feels. So design in this sense could be just as relevant to the ergonomics of a task chair to the layout of an airport queue.

We all know that Danish design is a thing, and not just for the convenient alliteration. I bet a lot of stuff you see in expensive furniture catalogs, especially the ones touted as “functional” or “mid-century modern,” were influenced by Danish design in one way or another.

When you consider the origins of the single greatest toy known to man and the fact that Danes always seem to be pushing what’s acceptable in post-modern architecture, it’s easy to see how Denmark can claim its position at the forefront of all things design today.

But as I spent more time on the ground, staying with exchange students who’d lived in Denmark for a semester and a Københavner who’d presumably lived in Copenhagen all his life, I realized that my attraction to the city was far more complicated.

But let’s start with what we can see and touch.

Design

I’ve just stepped off a 13-hour flight, wandering bleary-eyed through an unfamiliar airport in what feels like the wee hours of the morning (it’s really late-afternoon).

I manage to find my way to the airport Metro terminal and plant myself, beaten carry-on and all, in front of an automatic ticket counter. The rather polished counter happily displays a number of destinations, all of which vaguely sound like kitchen cabinets from an IKEA catalog. In sleep-deprived delirium, I mindlessly click through screen after screen of fascinatingly åccénted vøwéls while scanning the subway map overhead.

I’m staying with a few exchange students in Nørrebro. Thankfully, the Metro stop nearest them (Forum) is easily pronounceable and only two zones away. After a few false starts (the Metro counter takes only coins and credit card, though the latter somewhat reluctantly), I pay my 24DKK ($4) to get to the city center.

The Metro runs every 5 minutes during the day and every 20 minutes at night, so it’s your best bet to get to and from the airport. If you’re traveling with a lot of luggage, you might opt to hop in one of the many bright yellow E-class taxis for about 250-300DKK ($40-50).

But you wouldn’t want to miss out on the fully automatic wonder that is the Copenhagen Metro, boasting such pristine reliability it was actually honored as the world’s best Metro system two years in the running.

With pleasantly informative announcements – in Danish, then English – and its slick glass panels to prevent unwanted third rail encounters (while also doing away with the need for human operators), the Copenhagen Metro makes our comparatively decrepit C train seem laughably out of this world.

I mean, compare this:

To this:

You know what, forget about the taxis. They’re expensive here, and you don’t need them. For a prime example of Danish design just moments after you step outside the airport, take the Metro.

I didn’t really plan an itinerary for my week in Copenhagen, but I knew I wanted to explore the design scene I’d heard so much about. On the plane ride here, I’d worked together a rough list of museums recommended by respectable publications and friends alike.

As far as museums were concerned, Statens Museum for Kunst (also known as the National Gallery, but the Danish name sounds much cooler), DAC&, Nationalmuseet, and the Dansk Design Center had all floated to the top of my must-see list.

I’d also been advised to browse through a few high-end design shops like Illums Bolighus, Hay, and Designer Zoo that showcase the best of classic and new designs for people who apparently have unlimited disposable incomes.

“Just walk around. Actually, borrow a bike, it’ll be quicker,” one of my friends had said.

“What’s a Copenhagen Card?” I’d asked. “Is it worth it?” The city’s oft-advertised tourist card promised unlimited Metro rides, reduced admission to scores of museums (many of which were on my list), and attractive discounts on “restaurants, car hire and sights.”

“Nah, it’s a scam,” my friend replied casually. “And to be honest [the Metro] is an open system and I never pay for a ticket, but there are quite a few controllers about.”

Ahem, well. There you have it.

In defense of Copenhagen’s wonderful tourism bureau (no really, they’re called Wonderful Copenhagen), the Copenhagen Card makes sense for lots of travelers, especially families, since the price of one card covers up to 2 additional children under the age of 10. You could easily calculate whether a Copenhagen Card is worth it if you’ve planned your trip in advance.

As for my friend’s insight into Metro fares, I’ll decline to comment and just leave you with this …

While traveling, you are subject to the local laws even if you are a U.S. Citizen. Foreign laws and legal systems can be vastly different from our own and it is very important to know what’s legal and what’s not. If you break local laws while abroad, your U.S. passport won’t help you avoid arrest or prosecution, and the U.S. Embassy cannot get you out of jail.

-Your friendly neighborhood State Department

Speaking of the Metro, the ride from the airport to the city center takes only half an hour, and I soon found myself gliding (the Metro here is really nice, remember?) into the Forum station.

I’d written the address of where I was staying somewhere in my notebook, but it was momentarily lost in a sea of to-see lists, airline itinerary details, and a somewhat implausible trip budget calculation.

And in that very instance, amidst the chaos of not really knowing where I was going, my ever-drying contacts, and a punishing fatigue only a transatlantic journey in a middle seat could impose, I looked up:

I stopped. I stared, in almost certain disbelief.

I felt my head lift slowly, basked in the soft golden-LED glow of the transcending staircase nearby. I felt comforted, protected even, by the smooth, yet texturally-colored cassette concrete slabs that surrounded me. The weight, the stress, the uncertainty of this last-minute escape, slowly floated off my shoulders.

Do you see it? The source of my effervescent solace? The symbol of progress and of status, a nod to the old while embracing the future, the pinnacle of design – in every definition.

Okay, okay. I’ll stop.

Here’s a close-up of what I saw, taken by someone with clearly superior photography skills:

Wow. I mean, just look at this clock.

I’m not exaggerating when I say this clock set the tone for my entire trip to Denmark.

Yes, I did end up visiting all the museums and shops and sights and scenes I’d carefully researched and picked in advance.

How else would I have taken a picture of this wide-brimmed pilgrim hat during my canal tour:

Or the tastefully white-washed walls of the circular hall of mysteries in the Round Tower:

Or this artistic rendering of the political and social turbulence in 20th century Germany at the National Gallery:

And this twister-wall too:

I also checked out some of the design shops my friends recommended.

For example, I had the opportunity to briefly gaze at what appeared to be a filament bulb covered by an inverted glass bowl, yours for only $500, on Vesterbrogade Street:

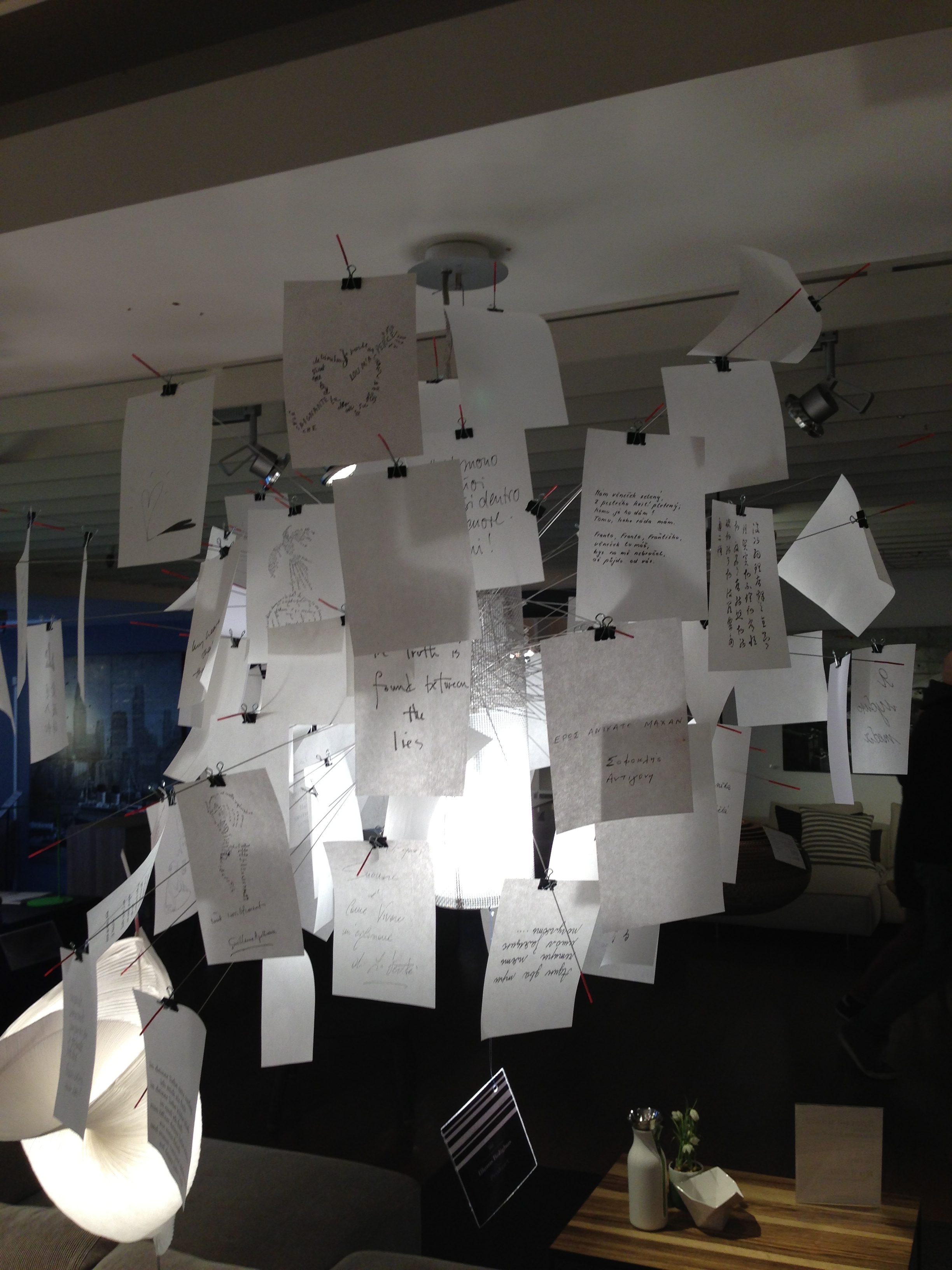

and appreciate a new kind of paper lampshade at Illums Bolighus,

and expand my definition of Good Design at Hay:

The museums I visited and the shops I perused were great, to be sure. But they certainly weren’t the only places to find good design.

To truly understand the concept of Danish design, I think back to the Metro clock. Design here isn’t defined by its price or position in a gallery.

In many ways, it’s the exact opposite. Good design fits seamlessly into our everyday lives, manifesting itself in objects that we normally wouldn’t bother with a second glance. It’s this attention to detail in craftsmanship, in all things, that makes this country truly unique.

So in that sense, the best way to experience good design in Copenhagen is by walking (or maybe biking) around the city.

For example, you might stop to admire this under-statedly sleek and energy-efficient stoplight:

Or ponder this choice of window shades at the Copenhagen Business School:

It soon became clear that design is truly democratic in Copenhagen. The city seems to put just as much architectural talent and resources into its new waterfront theater house:

To something as pedestrian as a parking garage:

Or student dorms:

I saw design better than what you’d find in any DWR showroom everywhere I went.

For the first few days, this universally utilitarian approach to design was quite confounding. How does Denmark afford to make everything look so nice? More importantly, why does this country so highly value such investments in design, architecture, and infrastructure?

The answer, I think, starts somewhere here:

Of all the museums and cultural sites I visited on my whirlwind tour of Copenhagen, I found the Danish Architecture Center (DAC&) to be one of the more under-rated sights in the city.

Nestled adjacent to the very same canals that pass more well-known landmarks such as The Little Mermaid and Amalienborg, DAC& is a shining testament to the Danish dedication to craftsmanship, to building things, and creating stuff.

The LEGO lab occupied just one floor of fascinating exhibits, but was the most popular by far. Every single table scattered about the room was surrounded by visitors, young and old and everyone in between, creating their next masterpiece:

This room was bustling with energy. And I couldn’t help but notice that the room was full of kids who couldn’t have been much older than when I gave my half-assed presentation on this country so many years ago.

Some of the things they put together were truly incredible:

Look, I love thinking about design (as if this super long section didn’t say that already). But even I’ll admit that design is inherently superficial.

I mentioned earlier that design primarily has to do with what you can see and touch, which is, by most measures, a fairly surface-level phenomenon.

Sure, there’s something to be said about how something makes you feel, but even that doesn’t do a great job in answering the harder questions of why something is the way it is. We can all feel different things about the same object, and that doesn’t bring us any closer to why or how that object came about.

I could think about design until the snaps run dry and hygge-friendly candles die out, and I still wouldn’t be able to answer any of the questions I posed earlier. Why are stoplights, Metro clocks, and parking garages so pretty in Copenhagen? Why are lamps so expensive? Why LEGO?

To answer these questions, I needed to look deeper into something much more complex.

Society

I may have creepily taken a picture of a random family walking through one of the more picturesque alleys of Strøget.

By now I’d spent nearly a week wandering about the city. I’d got a pretty good grasp of the city’s distinct districts, whether it be the posh streets of Østerbro or the grungier yet increasingly-hipsterized alleys of Vesterbro.

Everywhere I went, I saw families out and about, braving the sub-zero March cold to enjoy what scarce sunlight graced the city in a Scandinavian winter. A small boy intently watched his older grey-haired companions battle knights and queens on a worn picnic table in Nørrebro. On the other side of the city, I saw a gaggle teenagers deep in conversation, shouting and laughing, kringle in hand – just outside the closed-gates of Tivoli.

After days of being enamored by pretty buildings, sculptures, and stoplights, I slowly began to turn my attention to the Copenhagen’s actual inhabitants. You know, the living, breathing units of a community that really makes the city what it is. And I couldn’t help but wonder:

What would it be like to grow up in Denmark? What’s it like to be a Københavner?

Before we continue, let’s give fourth-grade me some credit here. Danes do eat lots of fish, often in the form of pickled herring on smørrebrød:

They do sail merchant ships of all kinds, though they’re hardly wooden nowadays:

And they are, by all American standards anyway, socialist:

Some people, my grade school teacher included, might find this last observation controversial. But it really isn’t. Not here, anyways.

Having stayed in Denmark for just over a week, I’m not really in any position to discuss the country’s government or greater political mindset in any meaningful detail.

But I did have an enlightening conversation with a Dane I stayed with towards the end of my trip. He was around my age and keenly interested in American politics. We were chatting over drinks when he jumped on the touchy subject of healthcare after he discovered I’d be tinkering around that space for state governments.

“So even though we don’t have universal healthcare, you’ll still get emergency treatment at most hospitals,” I explained. “It’s not like they ask for your credit card at the door.”

“But you still get charged in the end,” he pointed out.

“Well, yes. And that’s why you have health insurance. You pay a little bit every month in case you need to pay a lot more later.”

“Do you get health insurance from the hospital?”

“Not usually. They’re a lot of other companies that -“

“Private companies?”

“Right. These private insurance companies charge you a monthly fee to cover at least some of the hospital services if you use them.”

“So what does the government do?”

“Well, they cover costs for old people and poor people.”

“Oh! So the government does provide healthcare for everyone who can’t afford it.”

“Not exactly. That specific program is called Medicaid, and it’s only partially funded by the central government. The regional state governments actually run the program.”

“Just like here.”

“Er, sort of. But there’s only so much money that goes into Medicaid, and it doesn’t cover everyone who might need extra help,” I continued cautiously, lest I say something to embarrass oh great country of mine.”That’s partly the reason a lot of people don’t have health insurance in the United States.”

“So what happens if you get hurt and get charged a million hospital dollars when you don’t have insurance?”

I paused.

“Well, then you’re kind of screwed.”

“Just because you can’t afford insurance?”

“Yes, and also because some people don’t want it.”

“That makes no sense.”

“I’ll drink to that.”

We hadn’t gone into more nuanced topics like employer-sponsored insurance or tailoring premiums to disparate utilization patterns and care needs. But I also didn’t mention the frequently exorbitant hospital mark-ups over Medicare reimbursement rates and downright shady insurance practices either.

And at the end of the day, my Danish friend was kind of right. If you looked beyond rah-rah market economics and the enduring star-spangled banner of American exceptionalism, healthcare in the United States doesn’t really make much sense at all.

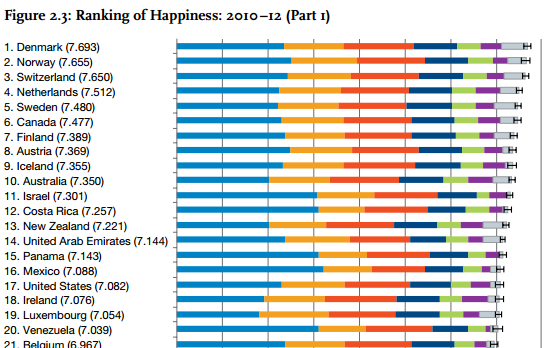

Denmark, on the other hand, boasts a welfare model that ensures all its citizens equal rights to social security.

Healthcare? Free. Education, including at public universities? Free. Generous unemployment benefits, 52-weeks paid maternity leave, and extensive public housing? Check, check, and check. A mandatory minimum five-weeks paid vacation for all wage-earners? Yeah, that too.

I glanced around my host’s spacious flat overlooking the Rosenborg Castle Gardens.

I silently guesstimated what I’d have to pay to enjoy comparably sumptuous living quarters back home in San Francisco. I quickly concluded that, for me at least, living subsidies alone would more than justify Denmark’s consistently tip-top ranking on the annual world happiness report. All the other stuff was just icing on the free-for-all cake.

Of course, few things on this planet are truly free. Danes pay for this incredibly high standard of living one way or another, mostly in comparably high tax rates.

On average, Danes pay nearly half their income back to state as a percentage of GDP. Though this figure doesn’t consider widely available tax deductions, it also doesn’t include the nationwide 25% sales tax (VAT) and an astronomical car tax for those who choose to drive. And all this tax talk doesn’t account for the costs welfare critics associate with lost productivity.

But the T-word isn’t thrown around like political cyanide as it is here in the United States. I mean, the country’s official website practically brags about having “one of the highest taxation levels in the world.”

Unlike the boot-strapping, make it or break it mentality out here in the United States, Denmark prizes socioeconomic security for all its citizens, regardless of where they come from – and what they contribute to the economy.

This universal safety net is wrought with a sense of civic duty extremely rare outside Scandinavia, even among the country’s like-minded European neighbors.

“I think you can ask anyone on the street and they will tell you that part of being Danish is taking care of other Danes,” observes a nurse in Copenhagen.

You can read the rest of her account and others’ in this excellent article on Danish governance and welfare.

In many ways, this deeply-embedded duty to society explains why Copenhagen looks so nice. Public infrastructure projects, whether it be libraries or Metro stations, are physical representations of the country’s devotion to national unity.

It explains why an excruciating level of craftsmanship is applied to all things, including everyday objects like a lamp or clock. It’s why Copenhagen has invested so much into its centers for the arts, sciences, and other things that further the enjoyment of life.

In the end, it’s how Danes feel, not just in Copenhagen but across the country, that inspires what you see.

Other

All this talk of the welfare state and socialistic tendencies might get you thinking that Danes are encouraged to think and act the same. And that view, while inherently misguided, actually doesn’t fall too far off the mark.

Case in point:

This is noma, a culinary wonder-world in the center of Copenhagen that elevates local flora and fauna into indescribably complex and refined dishes. The wait-list for a table lasts just as long as the number of weeks I’d need to survive on Netto cheese sandwiches to afford a wine-paired menu here.

Noma’s also been voted the world’s best restaurant an impressive number of times since chef René Redzepi opened its doors in 2003.

So imagine my surprise when I learned that local critics didn’t take too kindly to the place when it first opened. That’s right, critics initially panned René and his cohorts as “seal-fuckers” and a litany of other colorfully creative and maritime-inspired swearwords.

The trouble, it seems, was that Redzepi’s non-traditional approach to Nordic cuisine, coupled with noma’s upstart success, flew in the face of Janteloven, or the Law of Jante.

Coined by Danish author Aksel Sandemose back in 1933, the Law of Jante is a well-known Scandinavian principle that discourages individual success and accomplishment at the cost of the greater group.

Here’s a rough translation of the 10 rules, brought to you by our friends at PineTribe:

1. You’re not to think you are anything special.

2. You’re not to think you are as good as us.

3. You’re not to think you are smarter than us.

4. You’re not to convince yourself that you are better than us.

5.You’re not to think you know more than us.

6.You’re not to think you are more important than us.

7. You’re not to think you are good at anything.

8. You’re not to laugh at us.

9. You’re not to think anyone cares about you.

10. You’re not to think you can teach us anything.And the implied, and perhaps creepiest of them all, unspoken rule:

11. Perhaps you don’t think I know a few things about you?

Yikes.

On one hand, these rules just underscore the value of humility and collaborative accomplishment. You’ll find similar principles in cultures around the world, most notably in a Japanese proverb that warns of a severe hammering on the nail that sticks out above the rest.

On the other hand, these rules dump a giant Stalin-esque shit on individualism and the free spirit.

It’s true that I witnessed Janteloven here and there, from the city’s strict height limit on new developments to its inhabitants’ rather narrow income distribution. And when you consider that even cosmopolitan Copenhagen is a bit more racially homogeneous than let’s say, Queens – New York, you might even be tempted to think that Danes harbor suspicions about all things foreign.

But here’s the thing. If there’s anything I’ve learned during my two decades on this planet, it’s that people are people and you should generally let them be people.

And Copenhagen certainly wasn’t an exception to this rule.

Where else could I walk around, delicious shawarma in hand, and stumble across this little gem in Indre By:

And how could we forget about Christiania, whose inhabitants were keeping things weird long before Austin and Portland rolled around.

The idea of social oneness makes sense here, especially since Denmark derives a large part of its identity through national unity. It explains why most Danes don’t mind high taxes, a small price to pay for such a well-functioning society.

But at the same time, janteloven or the general abundance of tall white people doesn’t mean that Danish culture itself is homogeneous or stolidly traditional.

In fact, I found that it’s this very persistent perception of Danish conformity that drives a deep-rooted desire to think different. It’s what I heard from the Danes I met, anyway, though their confessions were frequently expressed through hushed whispers – as if they were letting me in on a shameful secret.

I’m not sure what to make of this private conflict between self and society, so I’ll just leave you with this:

In (some) conclusion …

This post started off as a list of things to do and eat while in Copenhagen. As proof of this, you can still read the original list at the bottom of this page.

I’m not sure how it evolved into my longest post thus far, but I suspect it has to do with all the fascinating things I saw, wisdom I heard, and feelings I felt during my short stay in the city.

Growing up in America, I heard a lot about what a young country we lived in. But as anyone who’s taken the J-Z train or gone to a pre-renovation public school in the 90’s can attest, this didn’t really mean much at the time.

It wasn’t until I spent some time abroad, especially in places like Denmark, that I fully appreciated the concept of national history.

One of the most striking things about Copenhagen is that you’ll find buildings like this:

stand right across the street from buildings like this:

But the sheer architectural diversity of this city is indicative of something much greater than oxidized bronze or smoked glass facades, I think.

The changes this country has seen and lived through, including all the ups and downs of the past millennium, makes for a truly unique society you won’t find anywhere else. And all the while, this capital city stays true to itself, silently reminding its citizens – both new and old – of what it means to be Danish.

Take in the history, see the sights, and meet the people of Copenhagen yourself. You won’t be disappointed.

DO:

- Canal Tours Copenhagen, 1h, 75DKK ($13), unbeatable views of the best aggressively post-modern architecture the city has to offer

- Statens Museum for Kunst (The National Gallery), 110DKK ($19), with everything from ancient spools to Twister-on-the-walls

- Illums Bolighus and Hay, if you’d enjoy aesthetically pleasing but shockingly expensive chairs and other sundries

- Christiania, yes – you should

- Rundetaarn (Round Tower), 25DKK ($5), the setting of this mysterious but inspiring stock photo

- Vor Frelsers Kirke (The Church of our Savior), 35DKK ($6), the views are better than at the Round Tower, though the walk up isn’t nearly as circular

- DAC& (Danish Architecture Center), better than any Lego store, 40 DKK ($7), free on Wednesday evenings (15:00-21:00)

- The Rosenborg Castle, the gardens are better

- Tietgen Kollegiet, to compare with your dorms from back-when, make friends to see the inside

- The Little Mermaid, it’s just a small statute; I don’t get it, but maybe you will

- Tivoli Gardens, the original Disneyland, 99DKK ($17), closed during the winter unfortunately

- Nyhavn, obligatory pictures, take the canal tour too

- Saint Petri Church, in the heart of the city, right next to the Church of our Lady

- The Copenhagen Zoo, more than just giraffes and lions, spend a nice day out in the surrounding Frederiksberg Gardens too

- Amalienborg Palace, the winter home of royalty

- City Hall, it has been described as “crazy awesome inside”

- Bike around, find the stuff you’ll like most

EAT:

- Kødbyens Deli, Fish & Chips, $ – not to be confused with Kødbyens Fiskebar, which is also great, but includes several additional $’s

- Smagsløget, Deli and bagels – native New Yorkers need not patronize (har har), $

- Madglad, Cafeteria, $

- Kebabistan, Kebab (surprise), $

- Ahaaa Det Arabiske Madhus, Middle Eastern, $

- The McDonald’s at Kongens Nytorv, to ponder over the thoughtful wallpaper, $

- Brød, mostly bread, $$

- Lagkagehuset, pastries, and yes, Danishes too, $$

- The cafe inside the National Gallery, Cafeteria, $$

- Nørrebro Bryghus, Brewery, $$

- Restaurant Schoennemann, Smørrebrød, $$$

- Royal Smushi Café, if Queen Elizabeth ate smørrebrød, $$$

- LêLê, Vietnamese, $$$

- Restaurant Bror, New Nordic, $$$

- Netto cheese sandwiches or one of the many AYCE ambiguously-Asian buffets to tide you over for the budget-busting that is sure to ensue if you go to any of the following:

- Geranium, Scandinavian, $$$$

- Kadeau København, representing cuisine from Bornholm, $^71

- Studio, idk, $^72

- noma, anything remotely edible within 100km of Copenhagen, $^∞

Editorial note: An earlier version of this post stated that it was common for a college-educated professional to pay more than 50% of her income back to the state. While this is possible under official tax rules, many readers pointed out that – after various tax deductions – it was more typical for Danes to have effective tax rates between 30-40% of gross income. This figure does not consider property, sales, or excise taxes.

Wow…thoroughly enjoyed reading this article. It is always nice to encounter things in reality those that we dreamed about in our childhood…in your case visiting Denmark. And you seem to have captured the essence of the country in the short time that you seem to have stayed there. You truly have the right spirit for travelling.

And you have a lovely writing style. Wish you all the best !

Thanks for reading – and the kind words!

I agree… wow, great article! I’ve just started a bucketlist so I can add Copenhagen! I will definitely share and look forward to reading more. ☺