Ever since I took my first job in college as a sandwich artist, I’ve been suspicious of the American reluctance to talk about money. The franchisee scumbag who hired me told me how much I’d be making, and told me not to tell any of the other employees. The message was clear: he was going to be paying the white, male, inexperienced college student more than the black, brown, undocumented and experienced employees he already had.

That experience stuck with me, and so I try to talk about money as frankly and explicitly as possible. And it turns out, most people are eager to talk about money! Sometimes that’s obviously a gentle form of humble bragging (“I’ve got a couple of small rental properties around town”), but more often it seems like people have a huge reservoir of topics they have been made to feel uncomfortable talking about, but are dying to ask about.

“What’s going to happen?”

This is the question everyone asks, and fortunately it’s the easiest to answer: nobody knows. The financial analysts have their models based on normal distributions and standard deviations, but the way I prefer to think about it doesn’t require any math at all.

Over any given period, the likeliest thing to happen is what happened in the previous period, and this tendency is more pronounced over longer period than shorter periods. In other words, on an hourly or daily basis financial returns are completely random, but over 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year periods the mild tendency for each period to repeat the previous period’s behavior becomes more pronounced.

The second likeliest thing to happen is for something to change. If yesterday the US stock market went up, it will probably go up again today, but it might not: it might go down instead.

The third most likely thing to happen is something crazy. In the last 20 years in the United States we’ve experienced a mismanaged terrorist attack, a mismanaged financial crisis, and a mismanaged pandemic. That’s about one economically catastrophic event every 7 years. Such events may become slightly more or slightly less common over the next 20 years, and slightly better or slightly worse managed, but it’s a reasonable place to anchor your expectations.

“How am I going to feel about it?”

This is the question no one asks, but the one that actually matters. Unfortunately, no amount of soul-searching is going to yield an answer. The only way to answer the question is to examine your real-time reaction to events when you have actual money invested in the outcome.

Each part of this equation is essential. Take the stock market crash between late February and late March of this year: from our perspective today, it looks like a sharp drop following by a slow, but steady, recovery. Before dividends:

- between February 19 and March 23 Vanguard’s total stock market ETF (VTI) fell 35%;

- between March 23 and December 8 it rose almost 72%;

- and between February 19 and December 8 it rose 11.59%.

In hindsight, this was a pretty uneventful period. The year to date return in 2020 of 16.46% is on the high side of US stock market returns, but not unusually so: according to Yahoo! Finance, since 2002 VTI has performed better in 6 years, worse in 11 years, and had an almost identical performance in one year (16.41% in 2012).

But it sure didn’t feel uneventful at the time! Stuck at home or forced to work in unsafe conditions, and seeing the stock market collapse alongside an ongoing mass casualty event felt like the end of the world.

So the question isn’t how you feel about the drop in stock market prices today. Obviously today you feel fine about them. You might even be bragging about how smart you were to “buy the dip.” The question is how you felt about them in March, and the only trustworthy way to know is verifiable contemporaneous accounts. I like using Twitter so it’s easy to check how I felt at the time:

- Here I am saying the stock market is not where you should invest short-term savings.

- Here I am saying stock prices are driven by a combination of the supply and demand of liquidity, and speculation.

- Here I am saying stock ownership is properly treated as a claim on a stream of future revenue.

These are very boring views — I got bored just reading them — but that’s not the point. The point is, they were boring views I know I held in real time during the stock market crash.

If you’re not a heavy Twitter user, this exercise might be more difficult, but it’s still worth doing. Do you have friends or family you talk to about investing? Go back and find the text messages, DM’s, Facebook posts, or e-mails you sent during this period and take a close look. Your “memories” of how you felt are totally useless: find out how you really felt. I promise you’re going to feel exactly the same way when the next crisis comes along.

“What should I do?”

This question is the synthesis of the two above. If you know what’s going to happen (capitalism will undergo periodic crises), and you know how you’re going to feel about it (ranging from ice-cold to full-blown panic), then you should be able to develop an investment philosophy that accommodates inescapable reality and human emotion.

For example, I hold a small position in Cambria’s Tail Risk ETF (TAIL). I know that this fund has a negative expected value, and holding it will reduce the performance of my portfolio compared to fully investing in the stock funds I also hold. This is, from a finance point of view, completely irrational. But I do it because owning a fund that sharply rises during stock market crises is a way to make my investment philosophy (buy and hold forever) compatible with my emotional tendency to panic during global economic crises.

Checking my Vanguard transaction history, I bought TAIL at between $19.70 and $20.65 per share between September 20, 2018, and May 2, 2019, for an average of $20 per share. I sold it between March 2 and April 6, 2020, at an average price of $23.15 per share, for a total profit of roughly 15.75%.

That would sound impressive, except it was only $110.25 in total profit! That’s because the point of the holding was never to turn a profit on the investment itself. It was to give me an investment I could be excited about selling during a global economic crisis, and it worked perfectly. Instead of selling my stock holdings which had collapsed in value, I sold a rapidly appreciating ETF and invested the funds in those newly-cheap stock funds. The stocks obviously recovered, with a helpful boost from the value of the TAIL shares I sold at the bottom.

The empty promise of behavioral coaching?

One of the things I’ve become more cynical about in the past 5 or 10 years is that we have the tools to manage people’s investment expectations and behavior. I always try to foreground not the possibility, but the certainty of stock market losses. And during a decade of stock market gains, everyone pretends to understand. But despite all my efforts, the second the losses begin, the panic nevertheless starts.

I suspect there are, roughly, only three kinds of investors: the gullible, the astute, and the hopeless. I don’t mean any of these terms pejoratively, just descriptively.

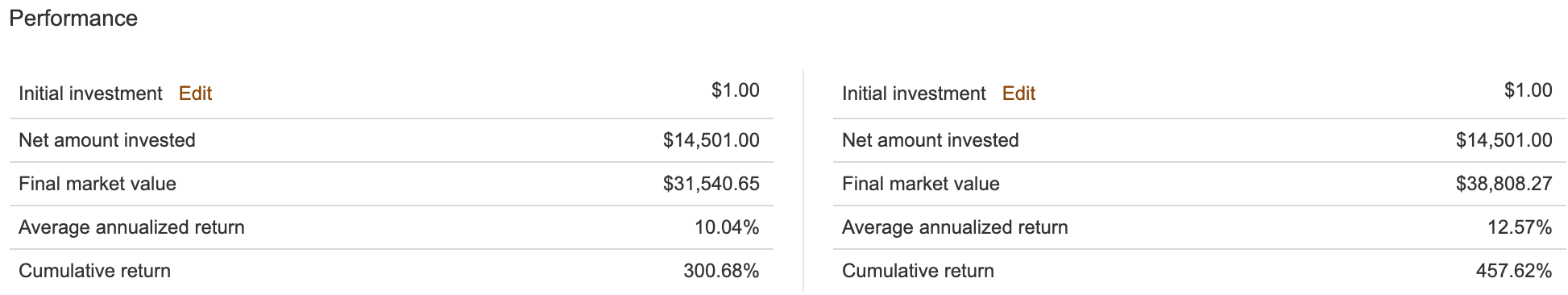

Gullible investors are those who know they need advice, either seek it out or are found by it, and take it. I suspect gullible investors end up with the best investment outcomes, not because the advice they receive is necessarily good or honest, but simply because they take it. To give a simple example, the Rydex S&P 500 C shares have a net expense ratio of 2.43%. This is utterly insane: Vanguard offers the same product for 0.03%. But nobody’s paid to sell gullible people Vanguard ETF’s. People are paid to sell Rydex C shares, and it turns out, they’re fine. Assuming quarterly investments and reinvested dividends and capital gains since April 2006, the absurdly expensive Rydex shares returned 10.04% and the absurdly cheap Vanguard shares returned 12.57%. The difference is a lot of money, which goes to the con artist, her supervisors, and their employer who sell the Rydex shares, but if a con artist is what it takes to get you invested, you ended up doing fine invested in the scam. Who is going to sneeze at 10.04% annualized?

Astute investors illustrate the timeless maxim that “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” The astute investor checks on her investments every day, because it’s the “responsible thing to do.” Just like a doctor does his hospital rounds or a dentist supervises her hygienists, the astute investor knows exactly what he owns and checks in regularly to make sure all is well. But of course, all is never well. When stocks are up, bonds are down. When emerging markets are down, developed markets are up. But unlike the doctor or dentist, there’s nothing for the astute investor to do! This leads to a kind of psychic tension, where the astute investor knows they must act, but no action is capable of addressing the real problem: they pay way too much attention to their portfolio.

Finally, there’s the hopeless investor, the one who needs help the most but is incapable of seeking it out, or if they do seek it out, incapable of internalizing it. The hopeless investor not only responds immediately and emotionally to every market movement, but also acts on it. He sells into crashes and buys into rebounds, locking in losses and excluding the possibility of gains. If you recognize yourself as a hopeless investor, then my boring opinion is that you shouldn’t bother. Open high-interest checking and savings accounts, buy CD’s and Treasuries with known, fixed interest rates, and save as much as possible. You’ll miss out on all the highs and all the lows, but your money will be there if and when you need it. This isn’t a case for despair: there are lots of high-interest checking and savings accounts out there! It’s just a case against investing in products you are not capable of using responsibly.

Leave a Reply